(CelebrityAccess) As the reader may already know, Baron Wolman, Rolling Stone‘s first true photographer, is launching a Kickstarter campaign for his book “Jimi Hendrix 1968/1970,” a very limited edition of all the photographs the famed photographer took of the guitar legend both onstage and in intimate settings.

CelebrityAccess talked to Wolman from his home in Santa Fe., N.M., not only about the book but about his life as one of the best-known music photographers in the Bay Area in the 1960s.

It’s hard to keep the focus on a book when talking to somebody who was just as happy to talk about driving in a Ferrari with Miles Davis to a boxing gymnasium plus who shot everyone who came into the Bill Graham universe, from The Who to Janis Joplin & The Holding Company to Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and, of course, The Grateful Dead.

came into the Bill Graham universe, from The Who to Janis Joplin & The Holding Company to Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and, of course, The Grateful Dead.

In fact, Wolman is preparing for next year’s (yet to be announced) 50th anniversary concert of Woodstock with a possible showcase of his work at another festival, Napa’s Bottlerock. It’s early days for such possibilities but, for right now, Wolman has a book to sell and, along the way, has a few choice words about the current, stifling climate that concert photographers face and Joe Hagan, author of “Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine.”

Obviously we’re calling you about the Kickstarter campaign.

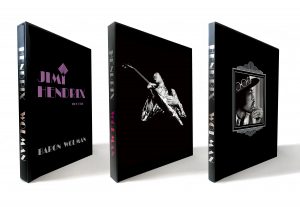

You mean the Hendrix book. It was the idea of my partner, Dagon James, who is a graphic designer, who actually designed the Woodstock book. I’ve done a lot of books but the Woodstock book is the most beautiful book I’ve ever done. So, I was not reluctant, whatsoever, to work with him when he proposed his idea to do a book of all my Jimi Hendrix photos. Every one of them.

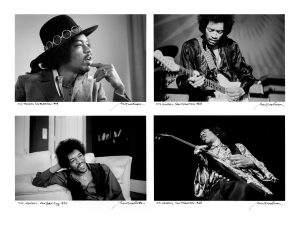

I photographed Hendrix four times. Two concerts in 1968 at the Fillmore West, one time with Jann when we interviewed him in his motel room and then another time when we interviewed him with John Burks who wrote for Rolling Stone around the time when Hendrix was deciding whether he was going to be Band of Gypys or not. He had had that idea but it hadn’t worked out as well as he wanted it to.

The fourth time I photographed him, we were sitting in the apartment of his manager, Michael Jeffrey. This was three months before he died and he was in a really good mood, very optimistic. They were just about to open his Electric Ladyland in the studio. He had all these plans for the future. And then he died.

It was a really significant meeting.

So Dagon James, my partner, said let’s do this book. We could have funded it ourselves but we thought we would try Kickstarter because both of us wanted to see how that worked. We wanted to see and see if we could reach people that way and give them some “extras.” When you get the book, you get a lot of bonus gifts, and we’ve kept adding new ones. As you know, Bill Sagan bought Bill Graham’s archives and turned them into Wolfgang’s Vault. He provided us with 100 original tickets to the concerts I had photographed. We only printed 750 books so the more expensive hundred copies get one of those original tickets. Interestingly enough, Sagan also has recordings of those two concerts. Originally we were going to include in the package a 7” vinyl with two songs from  those two concerts but the Hendrix estate said no since they claimed ownership of the applicable rights. Sagan argued that he owned them, but it stopped right there. It would have been so cool because you would have been able to tie in what you heard with what you are looking at, all those concert pictures I shot.

those two concerts but the Hendrix estate said no since they claimed ownership of the applicable rights. Sagan argued that he owned them, but it stopped right there. It would have been so cool because you would have been able to tie in what you heard with what you are looking at, all those concert pictures I shot.

But, well, the Hendrix people were not very cooperative. The music industry is so bizarre. Why be that way when you can be good guys? When I was shooting, I had all access to every concert, from Bill Graham in particular. Any concert he put on I could just walk around and do whatever I wanted. Now they limit the photographers to two or three songs in the beginning but – think about this – where are the most exciting photos? Toward the end of the concert. So, they’re losing the opportunity to have the best photographs of the concerts by limiting the photographers. And that’s just typical. The managers and the musicians just don’t seem to understand, or to care.

Now that you’ve brought that up, freelance photographers have complained about those limitations, and the forms they sign, and how, even if there are dozens of costume changes, the photogs get the same photos because of the three-song limit, etc.

I was at the right place at the right time. I was Rolling Stone’s first photographer so I could do anything. Back in the day, you had access to everything. At the time they needed Rolling Stone as much as Rolling Stone needed them. So everybody was cooperating. There was never a problem. My deal with Jann to be the photographer included my ownership of the pictures. Well, try and make a deal like that now! The copyright goes to the bands. It’s horrible.

Representatives for a lot of artists, especially country artists, will check out all of your photos and approve specific ones before you leave the venue.

Yeah, but look at this: how many cameras are in the audience? I mean, it’s stupid. Everybody brings an iPhone. Many people bring something better than an iPhone. They get great pictures. I mean, there are such short-sighted managers. A manager’s favorite word is no. That’s why I got out of it. When they started limiting access – do you remember the photographer Jim Marshall? He and I were probably two of the most well-known Bay Area music photographers. We were friends with the bands. We weren’t trying to take anything from them; we were trying to help their careers. But as the business of music became bigger than the music itself, the managers moved in and started hassling us. We just finally said, “Well, fuck you guys. We’re giving you something. We’re not taking from you. You don’t want us around? Fuck you. We’re going to leave. We’re not going to shoot anymore.” And we didn’t.

We were there in the halcyon days. If you look at my pictures in general. If you go on my website and look at the pictures, you’ll see how great the access was that I had to pretty much every musician that ever lived in those days. Same with Jim. And those pictures are memorable. I could go on and on.

Anyhow, the thing about this book that I think is interesting is that I’d not photographed Hendrix until those two concerts. I dunno, man. There was something about that band. I was so in sync with them. And it just surprised me that I could anticipate what they were going to do. I felt like I was playing my Nikons and they were playing their Fenders and Gibsons. I felt like I was part of the band in a way.

As a photographer, in those days, we didn’t have auto-focus and auto-exposure and all that stuff. And we had to shoot black and white for Rolling Stone because we couldn’t publish color then. I’d shoot 35, 36 pictures on each roll, make a contact sheet and I used to think, “Well, if I can get two or three shots, that will be good. That will be a successful day of shooting.” However, with the Hendrix stuff, on both concerts, I look at the contact sheets and there are 20-25 fabulous photos on all the contact sheets.

Something was going on and, to this day, I cannot explain it. Those are the best concert photos I’ve ever, ever taken. And that’s one of the reasons why we wanted to do the book.

Did you go with a Kickstarter campaign to try this new format or does it have to do with the current climate of traditional publishing?

Well, it’s very interesting. Until a few years ago I had a small press publishing company and I published a lot of my own books, and some other people’s books. I haven’t done that for a while but I don’t have any problem self-publishing.

But another photographer, Elliott Landy, self-published, with Kickstarter, a book on The Band. I don’t know how he did it, man, but he raised about $150,000 for that book. That’s why we gave it a shot. And we’re not having that success and we’re trying to figure out why. We’re getting some publicity, and we do our own marketing on Facebook and Instagram and all that stuff, but according to analytics, a lot of people are looking at the video but few people are buying.

shot. And we’re not having that success and we’re trying to figure out why. We’re getting some publicity, and we do our own marketing on Facebook and Instagram and all that stuff, but according to analytics, a lot of people are looking at the video but few people are buying.

We’re not sure what’s going on but we’ve made enough to cover our expenses. That’s the main thing. After the campaign is over the book will be available outside of Kickstarter. It’s not like we’re going to throw them away or anything like that.

It’s about $30,000 in pledges and $6,000 in wholesale, and that’s about the number we need to cover all of our expenses for everything we’re doing. And Kickstarter takes roughly 10 percent. They take about 7 percent plus the money Amazon charges for credit card. Right away, they take that off the top.

And we’re doing really cool things. We’ve tried a lot of interesting publishing variations to make it a really extraordinary book. It’s definitely going to be worth it. There are only 750 books. It’s going to be a collectors item. People who love Hendrix will definitely buy them. At least, I hope so…

Is it just photos? Will there be composition?

No, no, no! First of all, there are a lot of photos, right? And there are all of my contact sheets, so you see all of those. But, there are also my two early Rolling Stone covers are reproduced. Also my two articles that featured my Hendrix pictures in Rolling Stone, including the one where Jann did the interview with him. We got permission from Rolling Stone to reproduce those. The tickets are reproduced. The poster, which was very famous, called the “The Flying Eyeball,” done by Rick Griffin, who designed the original logo for Rolling Stone, is reproduced. It’s filled with a lot of interesting stuff.

Then there is an interview of me, by Dagon, reminiscing my Hendrix experiences, so there’s plenty to read, too.

Anything else?

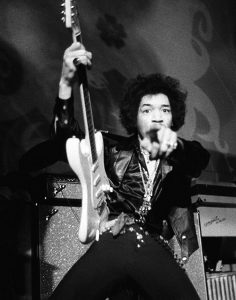

Two things I learned when I shot Hendrix. One was that I felt like I wasn’t taking the pictures but there was some force flowing through me that guided me. You know how people talk about being in the zone, creatively? That’s what I experienced. Being in the zone allowed me to anticipate the photos before they even happened. I can’t explain it other than that. If you saw a photo in the viewfinder you missed it already so you had to anticipate it and start shooting.

Also, what I learned in those days, is to pay attention to the music early on. You know musicians repeat their musical phrases and repeat their performance so, if you saw something you missed, you knew you had another chance. When you felt it was coming, you’d start shooting, not worrying about what you saw in the viewfinder.

That was important to learn and I learned how to get into the zone and how to get out of it. I had no idea it was something that you could psychologically do.

Any particular moments from those shows stand out?

I remember one. I shot two concerts. One I shot onstage. The other I was right in front of them. At the second one, Hendrix knew I was there and had been shooting for a while and there’s a moment where he pointed straight at me and acknowledged me. That photo I’ve always loved. He basically gave me a gift.

It was nice, man. Remember, this was 50 years ago. I don’t remember everything but, at the Fillmore West, it didn’t matter if you smoked pot or not because you’d get a contact high. And there was a light show going on behind. And then the music. So all of your senses were activated at the Fillmore West. They were great, great concerts.

Back then, though, wouldn’t it be “just” shooting “Jimi” versus shooting a legend? Not sure how to phrase it.

I know what you mean. Celebrity has a way of ruining the innocence of the musicians. I say that mostly of white musicians. Black musicians were always so appreciative of our interest in them and they would go out of their way to show that. The white guys’ heads got so big that it – well, like the way it is now. When you become a celebrity, you give away your solitude, your individuality, you have to almost give away the innocence of your personality. I don’t blame it totally on the musicians. I blame it on the whole genre of celebrity-ness, I guess. I think it’s very hard for a musician to escape the downside of being famous.

Hendrix, on the other hand, was really gentle. Hendrix was really intelligent. He was really aware of the social issues of the time. He talked about how difficult it was to be a black guy in a white world. He was so articulate. And the other thing about him – and I mention this in the book – is that it was impossible to take a bad picture of him. His style of dressing, the way he performed, everything was photogenic, I swear to God. I’ve never met anybody like that before.

Are you saying he’d be photogenic wearing the clothes he put on that morning?

Yup! The way he dressed, the clothes he chose. I’ll give you an example. When I photographed the first time at that motel room in San Francisco – the pictures are in the book – he had a hat with a hatband that had interlocking silver circles. I learned later that photographer Lynn Goldsmith was wearing a belt and he admired it, and she just gave it to him. He made it into a hatband. Who would have ever thought of doing that except someone who was aware of style? And the colors that he wore, and the scarves. We lost somebody very creative on multi-levels.

The recent Jann Wenner biography has caused some uproar and criticism. Do you have any take on it? Did you read it?

Oh, I read it. I talked to the guy. I thought he did Jann a big disservice. I didn’t like it. I thought he betrayed Jann. Jann gave him complete access to his whole life and records. What came out was a book for the TMZ crowd. OK, we know he did drugs, he could be a dick at different times. There was no question about that, and he admits it. But he kept that magazine going for 50 years in the face of lower circulation, higher costs. It is still an important publication but when he was running it, it was a very important publication. It was, for those of us who cared about the world, how we looked at the world. The stories on social issues were spot on, except for that one mistake toward the end, and the coverage of music was often prejudiced but still interesting to read. It was the best edited, in terms of editorial style, of any of the music publications. It was as well-written as the New Yorker. If you look at the style, he was very aware of the quality of the magazine.

No, I didn’t like the book. The best takeaway from the book that I got was this: when I quit Rolling Stone after about three years, I often wondered what if I had stayed, and I realized after reading the book there was no way I could have! In that sense, the guy did me a favor. But I thought he betrayed the confidence that Jann extended.

Those of us who were around had an investment in the experience and how it was represented. When I talk about it, I talk about having been there so I have a little more accuracy and investment in the truth. There were things I didn’t like and things I did, but his sex life and his drug issues, those were peripheral to the fact that the magazine came out every two weeks for 50 years. Come on!

The Kickstarter campaign is available here.