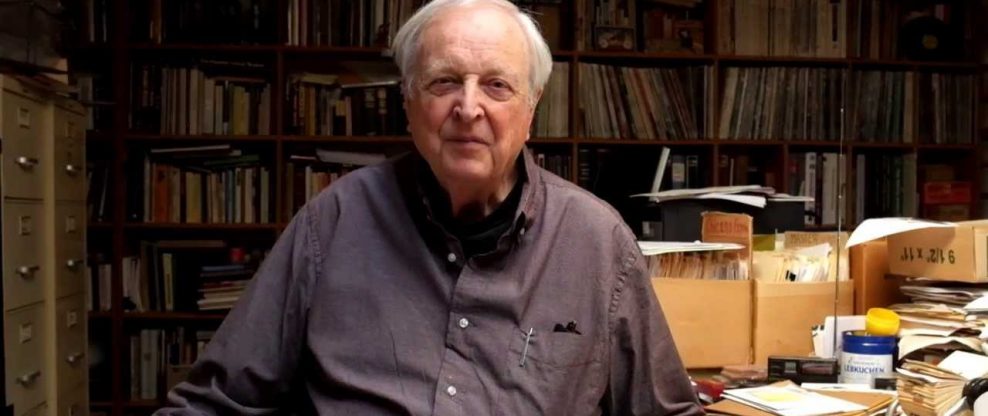

This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: Chris Strachwitz, founder, Arhoolie Records (1960-2016), & the Arhoolie Foundation (1995 to present).

At 90, Arhoolie Records/Arhoolie Foundation founder Chris Strachwitz is as vibrant as a Cajun played fiddle string.

Age hasn’t slowed Strachwitz down much, even if he’s now in an assisted living home, and unable to work at Arhoolie’s El Cerrito, California headquarters, due to COVID-19.

While he’s genial in conversation, every now and again an impatient, brilliant mind shows in its clearest color.

Since 2016, Arhoolie Records has belonged to Smithsonian Folkways, the nonprofit record label division of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

For over 60 years, Strachwitz captured and preserved America’s notable musical languages; ranging from Cajun, zydeco, Mexican-American, New Orleans jazz and brass bands, klezmer, polka, bluegrass, and gospel.

Primarily recording regional vernacular voices articulating uniquely American feelings, and thoughts.

First on 78 rpm records, and later on tape as performed in homes, backyards, front porches, gravel road, and backwoods clubs.

Among the musicians Strachwitz recorded were Clifton Chenier, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Mance Lipcomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Bukka White, Big Mama Thornton, Big Joe Williams Flaco Jimenez, Los Alegres de Terán, Los Pingüinos del Norte. Lydia Mendoza, and BeauSoleil who all continue to influence musicians today.

He also launched Back Room Record Distributors which soon changed to Bayside Record Distributors as a distributor of smaller independent blues labels.

Smithsonian Folkways has made more than 300 titles from the roughly 650-album Arhoolie catalog available digitally and is focused on ensuring that the remaining titles become available.

Born in 1931 in a village southeast of Berlin, Germany, Strachwitz was raised in an aristocratic family who lost most everything at the end of World War II when the region became a part of Poland.

His deceased grandmother had been an American, and her two sisters, concerned about the future of their niece, brought the Strachwitz family to America in 1947 to live in Reno, Nevada.

Sent to schools in southern California, Strachwitz became transfixed by the sounds of New Orleans jazz, R&B, blues, and hillbilly music he first heard on the radio.

Tall and good-looking, with straight hair swept back over a high forehead, Strachwitz became a familiar figure at folk, blues, Cajun, and zydeco events throughout America while recording hundreds of albums for Arhoolie Records.

Being lucky to be able to follow his passions all his life, as he frequently said in interviews.

Later, he became enamored with Mexican, and Mexican-American music

that led to him compiling a collection of historical recordings—now known as the Strachwitz Frontera Collection.

It is the largest repository of commercially produced, vernacular recordings of Mexican, Mexican American, and other Latin American music in existence. In addition, to its 170,000 recordings, the collection consists of over 25,000 photographs and over 700 hours of video tape.

Originally established in 1995 as a 501c3 nonprofit organization to protect and preserve the music of the Frontera Collection, the Arhoolie Foundation now has four staff members and has become a renowned archive of regional and roots music.

The foundation’s mission is to document and celebrate blues, Cajun, zydeco, gospel, jazz, Tejano/Norteño, old-time, and other tradition-based styles of music through archival preservation, community, and educational outreach, live performance, and direct support to artists.

Strachwitz is a member of the Blues Hall of Fame, an NEA National Heritage Fellow, and the recipient of a Grammy Trustees Award from The Recording Academy.

He is also the subject of a full-length 2013 feature documentary, “This Ain’t No Mouse Music,” directed by Chris Simon, and Maureen Gosling

I started collecting Arhoolie records in the mid-60s, and continued right through the ‘70s, and ‘80s. I likely own 200 of your recordings.

Oh my goodness, that’s amazing.

In articles over the years it’s rarely mentioned that you had a business partner, Tom Diamant.

Yes, he is still with me, and he’s part of the Foundation; although he’s no longer a paid employee, he helps me enormously. He worked with me until we sold the company to our wonderful patron, (philanthropist and musician) Ed Littlefield, and his Sage Foundation. Then he (Ed) gave it to the Smithsonian because the Smithsonian had no money to buy things like that. That is a distinction worth making. Also, Tom Diamant was getting so tired of contemporary distribution which was nothing but stupid little figures being shipped. It was just a pain in the ass.

You released 650 recordings, and the Smithsonian has digitalized about 350 of them?

Well, they keep them all available while they can. But all of the ones that I reissued you see, except the earlier 78s. They consider them not having the rights to them. But as long as they have stock on the ones that I reissued, they keep selling them. If they run out, they don’t make them available to customers anymore. That includes all of those Mexican and as well as Hawaiian recordings that I reissued.

After Moses Asch passed away in 1986, his family donated the Folkways’ catalog to the Smithsonian. Due to the Smithsonian’s novel agreement with the Asch family, every release from throughout the label’s history must remain in print, and be available to purchase.

That is one of the few labels still being maintained by the Smithsonian people. And, as I said, of course, they are still making Arhoolie recordings available. It’s no longer much of a business to speak of but the stuff is still out there, and still making some money from artists which was becoming a real headache. The royalty business is just insane because it is mostly downloads and streaming now.

The net streaming income derived Arhoolie recordings would be negligible.

Somebody gets money for something. You get a tiny, tiny fraction.

Your earliest recordings will be out of copyright at the end of the decade.

That doesn’t really matter.

You aren’t an ethnomusicologist, but nevertheless, coming from another language and culture, you saw American musical culture perhaps, from Tejano to Tex-Mex to blues to Cajun and zydeco, as distinct entities.

I don’t know how I was so lucky to get these people to co-operate with me and to greet me the way that they did. But I guess looking back at it, my size certainly helped. I’m a fairly tall guy. I’m 6’4.” But I think that it was also my enthusiasm that absolutely bubbled out of me because I knew their records beforehand. Most of the people who met me thought I was this crazy Gringo. One of the best singers and musicians (one of the great legends of border music) Ramiro Cavazos introduced me to his wife saying, “Signor Chris, El Fanatico de la musica norteño” (“The fanatic for Norteno Music”). But fanatico has a nicer connotation in Spanish. It means someone who is a real enthusiast about the music; who loves it.

If you hadn’t recorded some of these artists their music would have never been heard outside their own regions.

Well, I considered myself a sound catcher. I was lucky to be able to catch sounds that I heard when they (the artists) were at their height in their fields. That went for blues when it was really happening with people like Mississippi Fred McDowell, Bukka White, and Big Joe Williams. It was just extraordinary stuff. And the same for the Mexican and the creole music too. Zydeco, at first, was really exciting stuff, you know. It was really very pure creole music when I first heard it around Houston. There were these little groups that were playing, sometimes two accordions, and a washboard, and so on. Just that whole culture intrigued me

You had a great run in the ‘70s with French-speaking, Louisiana accordionist Clifton Chenier, recording his style of zydeco which arose from Cajun and Creole music, with R&B, jazz, and blues influences.

Growing up I was absolutely fixated by his Arhoolie releases, ”Louisiana Blues & Zydeco” (1965), “Bon Ton Roulet ! (1967), Clifton Chenier – Live” (1972), “Bogalusa Boogie (1975), and “Red Hot Louisiana Band (1977).“

You cannot not dance to this music.

(Laughing) Well, you want it (the story) from the start because that’s the lucky part. I was waiting with Lightnin’ Hopkins in Houston in early ‘64. We were waiting for (German promoter) Horst Lippmann who was running (with Fritz Rau) the American Folk Blues Festival. I was determined to get Lightnin’ to fly to Europe that year. Lightnin’ said, “Chris do you want to go, and see my cousin, Clifton Chenier?” It didn’t mean that much to me. I remember hearing Clifton’s 78 of “Ay-Tete Fee” (1955) on the Specialty label, but it was just typical R&B.

Anyway anywhere Lightnin’ would go, I went.

So we went to this little beer joint in Frenchtown (a section of the Fifth Ward in Houston), and the rats were huge crossing the road as we got there. Here in this tiny little beer joint was this tall, lanky black man playing a huge accordion, and there was just a drummer backing him, and he was singing the most lowdown blues I had ever heard. He was singing in this weird patois which I did figure out was some kind of a weird French. It was just gorgeous. It just totally knocked me out.

Were you previously aware of Creole music? By blending the older local rural Creole music with rhythm & blues, with a touch of rock and roll, and his unique personality, Clifton invented what today is known as zydeco music.

Yes, yes, yes, and I will tell you in a second, but you really have to remember this part. As soon as Lightnin’ and I walked in, Clifton saw us. Any white guy with Lightnin’ must be a record man. So Clifton immediately came over. “He said, “Oh yeah, record man, let’s make a record.” So we booked (Bill Quinn’s) Gold Star Studios the next day to make his first record for me.

I said, “Bring two of you over to Gold Star, and we will make a good record.” It’s a long story, but they weren’t any good. One of the guy’s damn amp started smoking, and it burned out, and the other one, the damn bass put out a put-put-put sound because the cone had separated from the speaker. So we just had the piano player, the drummer, and Clifton and that was basically it.

The only (track) we put out was “Ay, Ai, Ai.” It was never a huge song, but it was mainly in English. It got on the radio and Clifton was happy with it. It was on the local radio and they played it pretty soon after we pressed some.

Clifton’s “French” two-step recording, “Zydeco Sont Pas Sale” (with “Louisiana Blues” on the flip side) from the album ”Louisiana Blues & Zydeco” established him as the King of Zydeco.

Is it true that Clifton, believing no one would be interested in creole music, initially only wanted to record R&B in English?

Yes. I wanted to make an album the next year. I told Clifton, “I want some of that French stuff on that.” And, he finally agreed saying, “Okay, I will do half of it my way, and half of it will be the French stuff.” He figured it wouldn’t sell so well (if it was in French). Well, they did zydeco, and a track on the French side of the album, was that lowdown blues. Of course, being in French, I had no idea of what the name of it was. When I asked him after we cut it, he rattled off this French title. I asked, “How do you spell that?” He said, “Spell it any way that you want to.” After a few moments, I said, “Can I just call it ‘Louisiana Blues?’” Clifton thought a few seconds, and said, “Go ahead call it ‘Louisiana Blues.’” And it was probably the smartest thing that we did because DJs if they ever saw this French title on the label, they never would have played it. But they played “Louisiana Blues.” Nobody cared what the lyrics were. It was just this lowdown blues, perfectly recorded with good strong bass drum sound. It was just fantastic.

Soon afterwards Clifton and his Red Hot Louisiana Band played the Fillmore in San Francisco, Carnegie Hall in New York, and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Tours of Europe followed.

Was Clifton Arhoolie’s biggest seller?

At that time, he probably was, yes. It wasn’t that much later that I recorded an album by (harmonica player) Charlie Musselwhite (“Takin’ My Time” in 1971). He came out to California and was my packing man. He would haul stuff to the post office and to the docks to ship to Japan, and so on. I remember I did that album. He said he wanted that album. That actually sold better than anything else, but because he was white, I didn’t pay him that much attention. I was so stupid. Now looking back at the sales figures, he was by far my best seller for that year, and for the next year. Then (with their Southwest Louisiana music) came BeauSoleil in the early ‘80s.

You had a great run with Mississippi Fred McDowell, Bukka White, Juke Boy Bonner, Clifton Chenier, Charlie Musselwhite, Big Mama Thornton, and BeauSoleil recordings.

I was just a song catcher, really. I was never really a record label. I didn’t promote things that well. I tried to as much as I could, but I was hoping that the artist would find a good deal with somebody else.

And each of the artists I just mentioned did.

Unfortunately, Clifton got his Grammy for a much inferior record (in 1983 for his album “I’m Here,” the first Grammy for Alligator Records). It should have been for “Bogalusa Boogie that we did in Bogalusa (Lousiana).

Well, in 2015, the Library of Congress deemed “Bogalusa Boogie” to be “culturally, historically, or artistically significant,” and selected it for preservation in the National Recording Registry. The Grammys also recognized Clifton with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014.

Many of the later zydeco artists that followed Clifton pale in contrast.

They are of a different generation. They just will never get that feeling. There will never be another Clifton Chenier.

Cajun music has, however, fared much better.

That is Cajun music. Cajun music is much easier to keep the exact….(Cajun accordion maker, and musician) Marc Savoy says he is playing just the way the older guys he heard as a kid did. But that’s not so. He has definitely changed it, but not to the degree that the Creole music gets changed. What Clifton made out of that is just way beyond anything that has ever happened. Wayne Toups tried to do it in Cajun music. But that’s a totally different thing. I remember Clifton once told me, “Chris, you have to be a little ahead of people. You can’t be behind them. But you can’t be too far ahead of them because then they won’t like it. You better not be too far behind because then they won’t like you, at all.”

You recorded artists in their homes, on their porches, and in small clubs. What elements were you seeking? Authenticity? Sheer emotion?

It was basically that I didn’t want to spend money on studios. I never met them (musicians) in studios so I didn’t think of that. As a child almost, and for my whole career, I was totally in love with records. I thought that it (a record) was the neatest invention ever made because suddenly you could put the needle down on a piece of shellac, and out would come the most amazing sound. I have never forgotten that.

You became part of a loose younger network of blues enthusiasts that included Les Blank, John Fahey, Robert Crumb, Paul Oliver, Sam Charters, and others who trekked to the Southern states to record musicians.

Among the pioneers that had saved much of the American rural music history earlier had been Moses Asch, Harry Smith, Elliott Oberstein, Ralph Peer, Don Law, and musicologists, and folklorists, John, John Jr., and Alan Lomax.

I admired those guys. I learned about them all beginning with Ralph Peer with all that amazing, very early recording he did, even in El Paso. Texas.

El Paso was the center of the Southwest orquesta tradition which blended styles from Mexico and the U.S., including with the pivotal groups Orquesta Típica Fronteriza, and Orquesta Tomás Núñez. Groups often featuring 16-18 musicians would play polka, waltz, tango, and foxtrots often on homemade instruments.

Ralph Peer recorded sessions in El Paso, including in 1929 with the White Mountain Orchestra, featuring cowgirl singer Billie Maxwell, the first woman to record western music.

Of course, Ralph Peer had many sessions in Mexico, including with concert pianist Consuelito Velázquez, who wrote the international bolero standard, “Bésame Mucho.”

In August 1927, while talent hunting for the Victor Talking Machine Company, Ralph recorded both Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family in the same session at a makeshift studio in Bristol, Tennessee.

He also recorded Mamie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, and Perez Prado, and traveled throughout Latin America, publishing local songs, and expanding artists’ audiences so it was international.

As a producer, Ralph Peers and others were some of the first to record artists on-site, instead of taking them out of their environments and into an unfamiliar studio.

Him and Elliott Oberstein.

(A salesman under Ralph Peer at Okeh Records. In 1928, after Peer had joined rival Victor Records, Elliot Oberstein joined him there as a salesman and accountant. By 1930, he began overseeing recording sessions and set up his own company, Crown Records. After Ralph Peer left RCA Victor in 1932, Oberstein began recording country musicians in the South, establishing the Bluebird record label in the early ‘30s as a 35¢ low-priced subsidiary of Victor.)

By all accounts, Elliot Oberstein was a colorful wheeler-dealer.

I have never forgotten when I asked North Carolina fiddler J. E. Mainer, who recorded extensively for Bluebird in the 1930s, what he thought of Mr. Eli Oberstein who had followed Ralph Peer to the Victor firm, and who supervised almost all of those amazing regional musics, especially hillbilly, Mexican, and Cajun, and he said, “Oh, he was a great guy. He had a car full of whisky, and a pocket full of money.”

(Elliot Oberstein’s son Maurice “Obie” Oberstein was CEO of Polygram UK from 1985 to 1993, and before that was managing director and then chairman of CBS U.K. His signing include the Clash, Wham!, Sade, Psychedelic Furs, and Adam & the Ants. He served as chairman of the British Phonographic Industry twice, 1983-1985 and 1991-1993. The native New Yorker got his start at his father’s indie label Rondor and took over the business upon his death in 1960. Maurice “Obie” Oberstein died of leukemia in London in 2001. He was 72.)

In the era of the wind-up crank cylinder, “a car full of whisky, and a pocket full of money” is how a lot of label executives operated. They stocked up their automobile with booze and went into small towns seeking local musicians who were well regarded.

Well, it doesn’t hurt to have some money and libation.That is just what it takes. I guess that I was lucky.

California had a considerable hillbilly scene due to Okie migrations from 1935 to 1940, when people from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico sought farm labor jobs.

Correct. In 1947, I was sent to the Cate School and heard pure hillbilly music every morning over XERB from Rosa Rito Beach (below Tijuana) in Baja California It always beamed into L.A. which was full of Okies and Arkies at that time, and it was huge business. It was like there was nothing but country music.

XERB was playing hillbilly music because small indie labels like 4 Star Records and Columbia would buy time because the station reached up and down the West Coast.

XERB broadcast into the LA basin with 50,000 clear watts to the large Okie and Arkie population with hillbilly music on time bought–I later found out–mostly by 4Star Records, but also Columbia, interspersed with bizarre ads, like for a glowing statue of Jesus Christ.

So you heard hillbilly music like Hank Locklin, Webb Pierce, Cousin Ford Lewis, T. Texas Tyler, and the Armstrong Twins, Floyd and Lloyd.

Also the Maddox Brothers and Rose (known as America’s Most Colorful Hillbilly Band). All that good stuff.

Even then going against the mainstream, you played some of your 78s to your classmates, and they called you, “a damn hillbilly.”

I also became a total radio freak. Not only did I, and my friend at Cate School, Raymond Saint, write to XERB asking what it would take for us to become DJs at that station, and we actually received a reply: You had to be a Mexican national. I also started the campus radio station with my tiny oscillator which interfered with the other students’ radio reception. Then after doing amateur things on Pomona College’s station, I finally was heard in Berkeley over KPFA (on Pacifica network) with my own program for many years

Starting in 1965, and running to 1995, you had a bi-monthly Sunday program on KPFA, the first community-supported radio station in America.

I had a wonderful time doing that. I loved every minute of all aspects of it.

Meanwhile back in school, you also discovered New Orleans jazz music.

That’s what I started with. One day, my friend and classmate at the Cate School in Carpinteria, Bill Mellon, said, “Do you want to see this movie called ‘New Orleans?’” It was showing in Carpinteria. The school that I was sent to was a very elite boy’s school. I said, “Sure.” I had heard about New Orleans being interesting. Then I got totally hooked on the music in that film, “New Orleans.” It featured Louis Armstrong with the Kid Ory Band at the time which was in 1947, and it still had (trumpeter) Mutt Carey in it. A wonderful New Orleans band.

Mutt Carey left Ory’s band in 1947 to lead a group under his own name.

I asked Bill Mellon as we were walking back to the school, “What do you call that music that we heard?” He said, “That’s New Orlean’s jazz.” So I went totally bananas for New Orleans jazz after that.

(The plot of “New Orleans” was about a casino owner, and a high society singer falling in love in New Orleans during the birth of the blues. It featured Billie Holiday as a singing maid, and Louis Armstrong as a bandleader, performing together and becoming romantically involved. During one song, Armstrong’s character introduces his band, including trombonist Kid Ory, drummer Zutty Singleton, clarinetist Barney Bigard, guitarist Bud Scott, bassist George “Red” Callender, and pianists Charlie Beal, and Meade Lux Lewis. Also performing in the film were cornet player Mutt Carey, and bandleader Woody Herman.)

Then I just about flunked out of Pomona College because Frank Demond (a trombonist who would later play with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band and run his own record label, the Smoky Mary Phonograph Company) had a car, and he would drive us almost every night into Hollywood (before freeways) to the Beverly Cavern club. We were both fans of (jazz clarinetist) George Lewis and his amazing New Orleans Ragtime Jazz Band. They were getting really famous. That was a black New Orleans band that was this powerhouse rhythm machine, with a wonderful singing clarinet player They were playing a lot. I don’t think those guys ever made much money because they had to play every night, so many hours at these clubs. It was fantastic. We just loved that music. They were just like Gods to us. Oh, we were in heaven every night.

You bought records and brought them home. What did your family think of your interest in hillbilly and jazz music? You have told the story of listening to New Orleans’ jazz trumpeter Bunk Johnson, and your dad said to you in German, “They are playing off key.” And you replied, “It doesn’t matter to me. It’s got soul, it’s got feeling.” What did your family think of you being a music fan of this music?

Well, they thought that it was very strange.

I’ll never forget we were living with this very well-to-do great aunt in Reno, Nevada who was kind enough to put our whole family up in her house. I was catching this broadcast in the early ‘50s from New Orleans, which was called “Dixieland Jam Bake,” and they would have Papa Celestin & his New Orleans Jazz Band on the one hand, and Sharkey Bonano and His Sharks of Rhythm with Buglin’ Sam DeKemel. on the other. I will never forget my great aunt walking into the room where the radio was, and where I was listening to the ABC hook-up. saying, “My goodness, where is that music coming from? The Congo?” She thought it was most peculiar.

(Buglin’ Sam DeKemel, also a street waffle vendor, was known for his unique call that alerted people to his presence. He even caught the ear of a young Dr. John, who once said, “Buglin’ Sam may not have been a great bugle player, but he was one cranked-up loud one. When the kids heard him blowing his horn they came running from all around to fix their candy and waffle joneses,” spiked with Jones sausage.)

Much like how Europeans were drawn to blues and jazz music, it is more exotic coming from overseas. Even more so, if you don’t have full command of the language, as you didn’t when you were growing up, what you were hearing–uniquely American feelings and thoughts—would have been very exotic to you.

Well, I had never heard anything quite like it. I fell in love with all of these vernacular traditions in this country that I heard on the radio.

You were an avid collector of blues and jazz 78s.

My great aunt Janet was an extraordinarily wise woman. She realized that I had a passion for this stuff, and so she encourage it. She first helped me get a van to haul a bunch of 78s out of Georgia. She figured that I might become an antique dealer because that is what she knew about; that in San Francisco there was a street where there were a lot of antique stores, and records were always part of what they were selling. So she figured out what my passion was. She was very encouraging.

People today may not realize that 78s, which used a shellac resin, were quite heavy. In general, a 10-inch 78 rpm record weighed up to 110 grams. Carry around 20 or 30 78s around, that’s heavy.

The first time I drove to Brunswick, Georgia to pick up a stash of 78 blues records from this jukebox operator in the late 50s was in a laundry-type of small step-in van which my great aunt Janet helped me buy. I think it was made for a 1/4 ton load, max. I drove it back to Reno (Nevada) where we lived in her big house, but I must have had way over that weight because I blew out two tires. I probably had a thousand 78s in there.

When I drove to Texas in 1960, and to met up with (historian and writer) Paul Oliver in Memphis, I think I may have had a two-door Plymouth, and poor Valerie Oliver had to sit in the back seat behind Paul. On our way back to California, we were pulling a trailer and the car just couldn’t get over the summit east of San Diego. I had to hire a tow truck to get us over the mountain on that old two-lane highway.

Were you buying records to sell in California?

No, I was auctioning them off to the Europeans who were supporting my crazy hobby. It was to support my label which was financed a good deal by selling off blues records overseas because they (Europeans) really wanted them. I could buy them here for 10 or 20 cents, and they would bid up to $2 or $3 for some of them.

Was this after you launched Arhoolie Records in 1960 and began reissuing blues recordings by Big Joe Turner and Lowell Fulson from Jack Lauderdale’s Swingtime and Down Beat labels, and Bob Geddins’ Down Town label?

This was shortly after I started the label, and I had started buying records. I couldn’t afford any big new artists. I think one of my first records was by T. Texas Tyler.

Texas Tyler was one of the top country performers in the United States. I remember his 1948 hit, “The Deck of Cards,” as well as “Divorce Me C. O. D.” and “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It.”

He was billed as “The man with a million friends with his soul in his voice.”

You began to build a record company which was, in essence, always a hobby.

Well, I was lucky enough to follow my passion. Ralph Gleason, the late great reviewer here (who wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle, and was a founding editor of Rolling Stone), once told me,” Chris, you don’t have a record label. It’s your hobby.” And that’s very true. I only recorded things that I totally liked, almost exclusively.

In time, Arhoolie became an integrated music rights company by acquiring both recording and publishing assets. What caused that to happen?

Sometimes I took a hint from people from here and there. I learned how to make my own company that published songs that people had. It happened learning from Bob Geddins. He was a local producer here, a black guy in Oakland, who did some of the early Lowell Fulson records.

(Bob Geddins was largely responsible for developing blues in the San Francisco-Oakland area in the late 1940s into the late 1950s. He owned numerous independent record labels, including Art-Tone, Big Town, Cavatone, Down Town, Irma, Cavatone, Plaid, Rhythm, and Veltone. He also licensed his recordings to Swing Time, Aladdin, Modern, Imperial, Fantasy, and Checker.

After any reversal in his fortunes, Geddins would resort to his skills as a TV and radio repairman. Geddins produced the Rising Star Gospel Singers, the Pilgrim Travelers, Jimmy McCracklin, Johnny Fuller, Sugar Pie DeSanto, Etta James, Big Mama Thornton, Joe Hill Louis, and the Hi-Tones. A 4-CD box set of 107 of his recordings was issued in 2009 by JSP Records under the title, “The Bob Geddins Blues Legacy.”)

But it really was a guy in Louisiana at Goldband Records, Eddie Shuler who was a big help. He made some amazing records because he was in the right place at the right time.

(In 1952, Eddie Shuler established the Goldband complex—including a recording studio, and a record store and TV store in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and began recording R&B, blues, country, rock and roll, swamp rock, zydeco, and Cajun, building up a recorded catalog of over 10,000 titles.

Goldband’s hits included Boozoo Chavis’ “Paper in My Shoe” (1954), one of the first commercially available zydeco records; Phil Phillips’s “Sea of Love” which reached #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1959; and Cleveland Crochet’ & the Hill Billy Ramblers’ ’‘Sugar Bee,” the first Cajun recording to make it onto the Billboard Hot 100, reaching #80 in 1961.

Other notable Goldband artists included the Hackberry Ramblers (of which Shuler had once been a member), Cookie and the Cupcakes, Iry LeJune, Rockin’ Sidney, Jo-El Sonnier, and Freddy Fender. Goldband was the first label to record Dolly Parton with “Puppy Love”/“Girl Left Behind,” In 1959 when she was 13.)

I remember taking home one of the early tapes of a couple of black guys that were playing someplace that I had recorded. Accordion and washboard, I think it was. I played it for Eddie, and he said, “Did you get their songs?” I said, “Yeah, what do you think that I’ve got on that tape?” He then said, “No, that’s not what I’m talking about. Did you get the copyright for their songs?” I said, “Oh shit, what is that?” And Bob Geddins, when I asked him what should I put on my first 45s, he said, “Oh, just put down B-Flat Music Publishing.” That was his publishing company.

You recorded bluesman Mance Lipcomb in the living room of his little shotgun house near Navasota in Grimes County, Texas for what would become the first imprint on Arhoolie Records, “Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster.” You pressed up 500 copies?

No. We only pressed 250. We sold them all.

Did you sell the album mostly in America or did you sell them overseas too?

On the very first one, I don’t think that we sold that much overseas because, oh gosh this takes me back to how the whole thing started. Okay, I was a total Lightnin’ Hopkins’ fan from the early ‘50s when I went to college at Pomona in 1951 and I first heard his records on KFVD in Los Angeles. It was a tiny station, and Hunter Hancock’s “Harlem Matinee” two hours afternoon show, and he was playing black music.

For “Harlem Matinee” the intro was, “From bebop to blues, from jazz to rhythm, from vocal groups to here and there. And it’s Harlem Matinee.”

Texan Hunter Hancock, who was born in Uvalde, and raised in San Antonio, was the first on the West Coast to play R&B on the radio, and among the first to broadcast rock and roll. In Stan Freberg’s novelty song, “Rock Around Stephen Foster,” the record producer threatens, “You want me to tear up your autographed pictures of Hunter Hancock?”

KFVD rented time for all sorts of ethnic music, so I heard Jewish music and church music on Sunday nights from the St. Paul Baptist Church, whose theme song was ‘I’m So Glad Jesus Lifted Me.’ ”

By that time, it (KFVD) was just big orchestras like Count Basie or Duke Ellington but they were starting to play downhome blues, including Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Sonny Boy Williamson. All that music that was coming out. I was really taken by Lightnin’ Hopkins. I thought he was a total unique voice, and it seemed like he never did anything the same way twice. I finally met (music historian, writer, record producer, and musician) Sam Charters when I went to UC Berkeley in the ‘50s after I came out of the army in 1956. He was working on his first book “The Country Blues.”

So many of us music journalists back then bought “The Country Blues,” published in 1959. It is acknowledged as the first scholarly book-length study of country blues.

Correct. It was the Bible. He played me his records, and I thought that they were tinny sounding. They were all these early recordings that he had found down South. I went to listen, and I said, “I have a whole bunch of Lightnin’ Hopkins’ records, as well as Sunny Boy Williamson,” and so forth. He finally got close to the Lightnin’ Hopkins stuff, I guess. I will never forget in ’59, when I was starting to teach high school (teaching German and Social Studies for three years) at Los Gatos High School), I got a postcard from Sam Charters saying, “I’ve found Lightnin’ Hopkins. He lives in Houston, Texas.”

I literally took a pilgrimage that summer of 1959. I took a bus most of the way to Houston, and Sam said, “There’s a guy called Mack McCormick (the musicologist and folklorist) who is trying to be Lightnin’s agent.” He gave me his address.” So I met Mack McCormick down in Houston. I was staying at the YMCA, I guess. And I met Lightnin’ Hopkins. I was simply a fan. I had no idea of what to record with him. None whatsoever although I had been messing around with a little of tape recording and had recorded Jesse Fuller in Oakland, and K.C. Douglas. It was all very amateurish stuff. I was just happy to meet this guy. I was absolutely taken. When Lightnin’ took a liking to me he said, “Well come and hear me play tonight. I’m play at….” such and such a place.

And Mack knew where that was. It was just a little beer joint in one of the black wards of Houston.

So we went there, and I remember shortly after we came in, Lightnin’ was playing ferocious electric guitar with just a drummer behind him, and he pointed his long finger at me and sang, “ Whoa man, this man came all the way from California just to hear Po’ Lightnin’ sing.”

Lightnin’ wouldn’t know that within a year you would be a record man. You were just a fan who loved the recordings he had made. But he might have thought you being white in an all-black club was a promising sign.

It was because all of the other white guys that he’d ever met were either interested in recording him–record people who were making money off of him. But they were treating him fine. They were paying him his $100 a side, and that is what he was happy with. The other ones were people like Mack McCormick who would try to book him on folk programs. Folk music was becoming a big thing with John Lomax Jr. in Houston and all of those things. They got Lightnin’ somehow interested and made him some money.

Onstage, he’d tell stories of his life.

He just didn’t sing that line, he was also improvising how bad he was feeling that day; complaining extensively about how his shoulder was hurting, and the rain was covering the road, and his car having a hard time getting him to the gig because of the chuck holes in the road (“a hole or rut in a road”) because of the water covering them. He rhymed it all, improvised on the spot, and sang it. He made a damn blues out of it. Of course, parts of it, he had (previously recorded some of it. Like “I’m Aching All Over” on Herald Records (also released as “Sick Feeling Blues”). It’s a real tough blues. It was his improvising ability, all rhymed up, and backed by powerhouse electric blues guitar, and with a totally in synch drummer who followed and accented his every variation in the length of bars, that really grabbed me.

Lightnin’ Hopkins was an exceptionally original guitarist with a commanding vocal style.

Oh, yes. So I said to Mack on the way back, “God, I wish that somebody would record this man in a live setting like this when he constantly improvises.” I had no intention of recording Lightnin’ Hopkins. I loved the many records he had made. I was simply a fan. Only on the way back to Mack’s place did I, perhaps, think that I might be the one who would try and record him live.

Next year was 1960 and I bought a tape recorder (a poor quality monophonic Roberts recorder built in Japan by Akai with a single mike input), but it turned out that Lightnin’ was booked to play the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, and he was on his way with John Lomax who I didn’t know at all. So he was still there when I got to Houston but Mack and Lightning almost had a fight when Mack started talking about me wanting to record Lightning. Mack didn’t really like Lightnin’ that much anyway. He said, “Chris, you’ve got a car, why don’t we drive out in the country. There must be people like him out there.”

So we started driving toward Navasota. We had sort of become detectives by then. We saw a bunch of black people on the side of the road chopping the weeds of a field, and I went up to the fence and, of course, they came over, and one of them asked, “What are you all looking for?” I said, “Do you happen to know of any good guitar pickers in these parts?” He said, “You have to go to Navasota for that.” We thanked them, and we were on our way to Navasota. Mack was very knowledgeable about all of this blues stuff. Of course, we had heard that Lightnin’ Hopkins had made a commercial record on Gold Star Records, “Tim Moore’s Farm,” (1948). It was a powerful protest song. It is an amazing ballad.

(Tom and Harry Moore were notorious plantation owners along the Brazos River near Navasota who ran their classic tenant farm with mostly African American sharecroppers. By all accounts a heartless place of heartbreak, injustice, and psychological trauma. Some workers were trucked in for day labor; other families lived on the farm and were given a shack, a garden area, a cow for milk, chickens, and cash if needed. Of course, any loan or credits at the company store were owed back with considerable interest.

Over the course of its life, this song has existed in at least 6 versions. Lightnin’ Hopkins recorded it as “Tim Moore’s Farm,” which reached #13 on Billboard’s Most Played Juke Box Race Records chart in, 1949.)

At the time, I wasn’t taken by the record. I didn’t realize what an absolutely important record that it was. But when we got to Navasota, Mack said, “Anybody who knows anybody will be at a feed store.” So we walked to the first feed store that we saw. Mack was a gruff guy; he was like a policeman; he wouldn’t smile or grin. I didn’t say a word because I was such a (blues) fan. I would have totally blown it. He said, “Does Tom Moore happen to live in this town?” And the guy at the feed store said, “Mr. Moore sure does” Trying to put us in our place because we had said “Tom Moore” instead of “Mr Moore.” Mac said, “How can we get hold of him?” And he was told, “There’s a telephone right there, and he’s got his office right over the bank building.” Mack called him, and it turned out that he was happy to talk with us because he thought we were a pair of federal agents. He had gotten into trouble before.

So we went up there, and Mack almost instantly asked, “Mr. Moore can we visit your plantation?” He said, “Well, if you make an appointment I will take time out and show it to you if you need to see it.” Of course, we didn’t want to see it. Mack then suddenly asked him, “By any chance is there someone in this town that you like that plays music for people on weekends and parties?“ Tom Moore said yes there is this guy, and everybody seems to like him. But he didn’t know his name. He said, “Go down to the railroad station, and find Peg Leg. I’m sure he can give you his name.” So we went to the railroad station. We didn’t have much trouble finding Peg Leg, and he gave us the name Mance Lipscomb, and he told us where he lived.

So we went to Mance Lipscomb’s house, but he wasn’t home. His wife said, “Yeah, he’ll be back around 5 o’clock.” So we came back at 5 o’clock, and there he was. He had just got off the tractor cutting grass along the highway. He was just the sweetest, kindly elderly gentleman that I had ever encountered.

At first, you weren’t crazy about Mance because he played traditional songs and not the guttural, mean blues like Lightnin’ Hopkins, but the musicality was there. You told him that you and Mack wanted to record him

I was not that impressed with him because he was no Lightnin’ Hopkins. He was no ferocious blues singer. We asked if he would sing us some blues, and he did something like the “St. Louis Blues” and “Shine On Harvest Moon.” And Mack said, “Have you ever heard of a song called “Tom Moore’s Farm?” He said, “Oh, you want the real stuff. Well, I don’t want you to put that on my record while I’m alive in this town.” So I said I definitely don’t want to do that if you can give us your version, that would be historically really interesting.” And he recorded it for us.

Racial tensions in America afflicted communities large and small in every region of the country for decades. The late American civil rights activist and educator W.E.B. Du Bois spoke of trying to bridge the solitudes. “The problem of the 20th Century is the problem of the color-line,” he once said. The concept of the color-line refers essentially to the role of race and racism in history and society

Did racism impact you working in the American South?

Yes, but since I was basically, or half anyway, European, I was never that much into politics at all, and that’s the way things were. We (my German family) grew up under Hitler, and that’s the way it was. But yes, I did see it, but it really didn’t hit me, I felt it in Oakland (California) when the cops once stopped us on the way back from West Oakland which was all black. They pulled us over, and asked, “What are you doing here?” We said, “Well, we just went to this club to hear a band.” I think we asked them, “Why did you stop us?” And they said, “Usually, if there’s white guys going down there, they are either interested in prostitutes or in booze. We said, “No we just wanted to hear some music.”

At the time, the economic decline in Oakland West was characterized by unemployment, poverty, and urban blight.

We were pulled over because we were coming out of West Oakland which is kind of a black ghetto area.

It is unfortunate that this country still has to suffer from this whole slavery thing. It is absolutely horrific. And it doesn’t seem to want to go away. It is so hard to change peoples’ mindset once they are that deep into that stuff, you know. I’m just reading this amazing book called, “The Journal of a Resident on a Georgia Plantation in 1838 to 1839,” by Frances Anne Kemble. She was a very wealthy actress in Britain who fell in love with an American in Philadelphia. She thought he was a nice guy, and he was well to do. He had a huge plantation in Georgia, and the book is about what it was like to talk to these slaves.

(Originally published in 1863, and out-of-print for almost a century, Frances Anne Kemble’s journal has long been recognized by historians as unique in the literature of American slavery, and invaluable for obtaining a clear view of life in the antebellum South.

Kemble was one of the leading lights of the English stage in the nineteenth century. During a tour of America in the 1830s, she met and married a wealthy Philadelphian, Pierce Butler, part of whose fortune derived from his family’s vast cotton and rice plantation on the Sea Islands of Georgia.

After their marriage, Kemble spent several months living on the plantation. Profoundly shocked by what she saw, she recorded her observations of plantation life in a series of journal entries written as letters to a friend. But she never sent the letters, and not until the Civil War was on and Fanny was divorced from Pierce Butler, and living in England, were they published.)

Music from Mexican American, Cajun, zydeco, and rural blues cultures were firmly regional in the ‘60s and viewed in some quarters as relics of the past.

While the world today celebrates the blues today, in the ‘60s blues– Delta blues, hill country blues, and Piedmont blues–held little interest for African Americans despite being enthusiastically embraced by audiences, and musicians overseas.

As B.B. King wrote in his 1996 autobiography “Blues All Around Me,” “It makes no difference that the blues is an expression of anger against shame or humiliation. In the minds of many young blacks, the blues stood for a time and place they’d outgrown.”

At the same time, Cajuns were ashamed of their music. They wouldn’t admit to a non-Cajuns they were going to a dance; they used to call it chinky-chink music.

When Cajun fiddler and singer Dewey Balfa, the last surviving member of the Balfa Brothers, trekked north from Louisiana to appear at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, he was slammed back home for taking “chinky-chink music” to outsiders.

(Since then Cajuns have developed a pride among themselves, and appreciation in “chinky-chink music” has changed. Balfa was a recipient of a 1982 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is the United States government’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts. That year’s fellowships were the first bestowed by the NEA.)

For decades Mexicans lived in America in a backwater existence as White America saw them solely as a source of cheap labor. Despite Mexican and Mexican American culture being very rich, it has long been marginalized or looked down upon in media coverage.

Many American music fans would be surprised to know that Mexican musiciansAndrés Berlanga Y Francisco Montalvo were recorded by the ARC recording crew of A & R man Don Law and engineer Art Satherley in a San Antonio hotel room in 1936, alongside iconic bluesman Robert Johnson.

All of the folk festivals I’ve been to over the years, I have only once seen a Mexican American band play.

Okay, I can tell you what I did here in Berkley. In 1970, I had known, of course, Barry Olivier who was putting on the Berkeley Folk Festival (as director, and he also gave John Fogarty his first guitar lessons) every year since the late ‘50s. I told him I knew this norteño band from Mexico, they live in San Jose, Los Tigres del Norte. So he hired them, and they have become superstars.

(Los Tigres del Norte, whom corrido scholars consider the Rolling Stones of norteño music, played on a Berkeley Folk Festival bill with Big Brother & the Holding Company, Big Mama Thornton, Joy of Cooking, and Nick Gravenites at Pauley Ballroom in Berkeley on Oct. 8th, 1970.)

Los Tigres del Norte’s leader Jorge Hernández (lead vocalist, and accordionist) is an extraordinary guy. He realized that I had this amazing (Mexican and Mexican American) collection. For example, they were making a record in a recording studio in Berkeley, and they were doing a song about the Orphan Boy. I said that I had a two-part version made in 1928 in San Antonio, (“El Huerfano (The Orphan Boy”) by Trio Matamoros on Okeh Records. They simply were not aware of any of those songs had been recorded before they learned them from other singers in their village that they came from. He was totally unaware of that.

The concept of local musicians recording was strange for most people decades ago. So far removed from their day-to-day life. Not just in small regional communities, but also in urban and suburban settings.

In the case of the black music, that was, of course, hugely popular. Blues and gospel music, and all that kind of thing.

To watch Les Blank’s 1968 documentary film “The Blues Accordin’ To Lightnin’ Hopkins”—his second musician documentary; the first being “Dizzy Gillespie” in 1964—was an exciting experience.

Yes, it was exciting. I think that I first encountered Les when he had just made the film about Lightnin’ Hopkins because John Lomax Jr,, Alan brother who lived in Houston, helped him with that. Then Les knew that I knew Lightnin’ quite well by that time.

I love the scene in “The Sun’s Gonna Shine” (1969) of Lightnin’ singing about playing cards with Les Blank, and director Skip Gerson–a card game he won which turned critical to the making of the film “The Blues Accordin’ To Lightnin’ Hopkins.”

https://youtu.be/7RZo10xxKUY

(Les Blank’s music documentaries, including “A Well Spent Life” about the life of Mance Lipcomb (1971), and the Louisiana-base films “Spend It All” (1970) “Dry Wood” (1973, and “Hot Pepper (1973) were pure art, and they captured the essence of the rural and post-rural life in the Louisiana- Texas music belt.

Blank is, perhaps, best known for his feature-length “Burden of Dreams” (1982), documenting the chaotic production of fellow director, and friend, Werner Herzog’s 1982 film “Fitzcarraldo” in the jungles of South America.)

In 1976, you traveled to South Texas with Les and a young Ry Cooder to record the original giants of Tejano music in what would become the documentary film, “Chulas Fronteras,” a documentary about music on the Texas-Mexico border which was followed by “Del Mero Corazon” three years later.

(Chulas Fronteras” is a film by Les Blank and Chris Strachwitz, Conceived, produced, and sound recording by Chris Strachwitz. Cinematography and editing by Les Blank. Assistant editing by Maureen Gosling. Consultant: Guillermo Hernandez.)

I was the producer, co-director, and sound recordist plus locator of all the musicians and interesting people, and generally arranging everything.

Arhoolie underwrote the soundtrack?

I was Arhoolie Records, and so, I simply issued the soundtrack on my label. I can’t call it underwriting.

(“Chulas Fronteras” was among the first 125 essential motion pictures selected by The Library Of Congress to be added to the National Film Registry list, to be preserved in perpetuity.)

(“Del Mero Corazon” was a film by Les Blank, Maureen Gosling, Guillermo Hernandez, and Chris Strachwitz. Edited by Maureen Gosling).

Again, I was the producer, sound recordist, and so on.

You established Down Home Music as a brick and mortar retail outlet in 1976, making the records on one side of the building, and selling them on the other side, along with music from other folk-related labels. Was it hard getting your own records into retail record stores?

Mance came out to California in 1961 because he was on the Berkley Folk Festival. So many people heard him, and I was able to sell some LPs and then stores also wanted the LP. The next year when he returned more clubs wanted him, including the Cabale Creamery in Berkeley and the Ash Grove in LA. and, of course, the music stores knew about him I have that nice photograph of Mance that I took of him at the Greek Theatre where I was behind him and he was sitting up there with his hat on the floor. A lot of people heard him for the first time, and so they wanted his records, and we sold a few right off the bat.

You continued selling overseas over the years?

We used to export a lot. Europe was first, as I recall, mostly England. The Japanese, of course, licensed things from us. and the French also did eventually. And I was importing a lot of stuff from Europe and it was making our distributing company really wealthy. Everybody was getting good wages and health insurance and I was drawing a juicy salary because Tower Records would take anything that we got that was not available here.

Retail stores mostly worked on a consignment basis with non-pop product. If there were limited sales, they’d soon return the goods.

Yes, the distributors would do that. That’s true. And some of them were gangsters. We had one guy who was a rich doctor in New Jersey who screwed us all. It was fun to deal with the good guys.

Bear Family Records in Germany still exist by specializing in reissues of archival country and western, rockabilly, and Americana. A market still exists.

As I said, I was lucky to catch these musical traditions although it started with just recording them and then, of course, I took photos. I had to do that. Then, when I met (documentary filmmaker) Les Blank. I finally had some money by the time we did “Chulas Fronteras” and “Del Mero Corazon,” a superb era in the evolution of Tejano or Conjunto accordion music, one captured at the time and even that has totally changed in San Antonio. It has evolved into something that is nowhere near what it was.

How did your publishing company, Tradition Music Company come to own the copyright of “Country Joe” McDonald’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” recorded by Country Joe and the Fish, stalwarts of the blossoming psychedelic rock scene of the West Coast?

I had a good friend ED Denson (a music columnist for the Berkeley Barb who later co-founded Takoma Records with guitarist John Fahey, and Kicking Mule Records with guitarist Stefan Grossman). I was really lucky because ED Denson brought them over to my house, just before I was leaving to Europe with Lightnin’ Hopkins in 1964 on that American Folk Blues Festival (along with Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, Sunnyland Slim, Willie Dixon, Sleepy John Estes, and Sugar Pie DeSanto).

Oh my God, this motley crew of hippies, I just hung one of the directional mics from my lamp ceiling, and I put another mic under the wash-tub bass and put them around in a circle. I had two microphones. I’m not sure how the hell I mixed it.

Really primitive.

All the money first came to Tradition Music Co., and then I paid Joe his 50%. I also inserted the manager’s name. ED Denson (today a well-known attorney), who really had helped me a lot to copyright compositions (under their actual names) by many of the performers I had recorded in order to protect their rights, since most had no idea what publishing was all about.

It was a verbal agreement.

Of course, at that time, the deal was usually 50/50. If you signed up somebody with certain songs, whatever money came in you split it 50/50 with the composer.

In essence, the writer retains the author’s share, while you have the publisher’s full share.

Yes, it was the publishing part. So we split whatever came (50% to my Tradition Music Company, and 50% to the composer Country Joe McDonald). The first check for $70,000 came in after Woodstock made it famous, and I put my money down on my building, and I sent him his $35,000. At first, he was really kind of pissed that he did this, you see, because he kind of knew then what publishing was and on and on.

“I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” which originally appeared on a 1965 7″ EP “Rag Baby: Songs of Opposition,” made you a great deal of money over the years.

Country Joe and the Fish played Woodstock, and the song was in the movie of the same name, as well as “More American Graffiti,” (1979), “Purple Haze” (1982), “Hamburger Hill” (1987), and the HBO miniseries “Generation Kill” (2008).

So you each made a lot of money.

Yes, I did. I also did a good deed about 20 years ago. He (Joe) came to me and said, “Chris don’t you think that you made enough money off of me?” I said, “Yes Joe, you are a good socialist. I will give it (the song) back to you.” His stuff wasn’t really doing much anymore. So I gave it back to him, but he had lost all of the stuff (paperwork) that I gave him. He had lost all of those papers from the British society (The Performing Right Society) where they had cleared it. First, they had problems clearing it in Europe because the British Society is very careful. They listen to stuff and they felt that there was a chance that it had something to do with “The Muskrat Ramble” by Kid Ory, but they cleared it.

Not that long after I had given it back to him Kid Ory’s daughter sued Joe McDonald claiming that he had stolen that song from her father.

I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” did face a legal challenge from Babette Ory, Kid Ory’s daughter from his second marriage, and heir to the “Muskrat Ramble” copyright. She sued Country Joe McDonald for copyright infringement in 2001. She claimed that Joe had appropriated the melody for “Muskrat Ramble” as recorded by Louis Armstrong & his Hot Five in 1926. A 2005 judgment by Judge Nora Manella, of the United States District Court for the Central District of California, upheld McDonald’s copyright on the song, claiming that Ory and her father were aware of the original version of the song with the same questionable section for some three decades without bringing a suit. They had waited too long to make the claim. This ruling was upheld by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 2005, and Ory was ordered to pay McDonald’s substantial attorney fees.)

The judge threw it out. She said, “This is a mean-spirited attempt,” and asked Kid Ory’s daughter, “Why did you wait so long to do this?”

So I was so lucky to have given it back to Joe because my pockets at the time were probably much deeper than his. He got a really nice attorney, a civil rights guy, and the suit was thrown out. But if I still had had that copyright, I have no idea what kind of problems I would have gotten into. I gave a deposition at the time telling them that I vividly remembered that the British clearing society had sent me a notice saying, “This is sufficiently original to warrant them claiming the copyright for Joe. As I said, he had lost all of that paperwork. At least I gave a deposition during the trial.

In another case, you went after the Rolling Stones for copyright infringement of “You Gotta Move” from their 1971 “Sticky Fingers album. Reverend Gary Davis had recorded the song in 1962, and Mississippi Fred McDowell used lyrics close to his rendition but added a distinctive slide guitar line.

Often you’d see the song listed as a traditional African-American spiritual song, but eventually, it was credited to Mississippi Fred McDowell.

We were lucky because on the first pressing, I’m not sure about subsequent ones, on that zipper cover you see the composer printed in parentheses under the title. But somebody in the Stones, I don’t know who it was, I think it was the guitar player (Mick Taylor) he said it was Fred McDowell (in an interview), Of course, when the manager of the Rolling Stones heard about my claim that I had publishing on Fred McDowell’s version of that song, he said, “No no, Anything the Stones record is their own stuff.” Well, we did have to file a suit against them.

The Rolling Stone finally agreed to credit and pay Mississippi Fred McDowell, and you gave him the biggest cheque he had ever had, When you did, he reportedly said, “I’m glad them boys liked my music.”

(Sadly, Mississippi Fred McDowell died of cancer in 1972 at the age of 66 The rear side of his headstone reads, “You may be high, You may be low, You may be rich, child, You may be poor, But when the Lord gets ready, You got to move.”)

Reissues of “Sticky Fingers” have listed Fred McDowell as the composer of “You Gotta Move” but sometimes Reverend Gary Davis is listed instead.

What happened was that Manny Greenhill (of Folklore Productions) who was the manager of Reverend Gary Davis, and I knew him well, he called me, “Chris, Fred McDowell didn’t write that song called “You Got To Move.” The Reverend wrote that.” Well, he had recorded a version of it in his guitar picking style, while Fred McDowell played it very differently on the slide guitar. I said, “Manny, you and I both know this is not an original composition. This is an old traditional Black hymn, a spiritual,” and he said, “Okay. Why don’t we get together and whenever somebody records Fred McDowell’s version, he will get three-quarters of it, and the Rev gets one-quarter. And if they ever record the Reverend Gary Davis ‘then he gets 75% and we get 25%.”

In the past, when an artist recorded a traditional song and didn’t claim authorship, many labels would claim the copyright or part of it.

I know that fact because of working in the Mexican field. There’s an old corrido dating from the mid-20s or even earlier called “Contrabando Del Paso,” recorded by Ralph Peer for Victor on his first trip to El Paso, and there’s this woman who has been doing exactly that. She has been putting her name on all kinds of stuff. And she sent me a cease-and-desist or to get a share of the money. They wanted the copyright.” I said, “Dear lady, I have a record that was made in the mid-20s of that song; that was even before you were born.” I never heard from them again.

Did you ever marry?

No, I never found the right person. That was one of my problems. But that is the way it went. I was never able to get a family. Something told me inside about this one woman that “You can’t live with her.” There was something inside of me that told me. That is what happened.

And as Texas honky-tonk troubadour Ernest Tubb warbled in 1948, “That’s all she wrote.”

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is a co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.