(Hypebot) — Bill Werde offers some much-needed context to the recent music industry hysteria over AI-generated music.

A version of this essay first appeared in Bill Werde’s free, weekly Full Rate No Cap email. Werde is a former Billboard Editorial Director and Director of The Bandier Program for Music and the Entertainment Industries of the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University.

Last week woke the world when it comes to the potential and the immediacy of AI. As any reader of FRNC surely knows, an anonymous producer Ghostwriter977 cooked up a solid-enough beat, wrote some pop-culturally savvy lyrics, and then used AI to produce the track, “Heart on my Sleeve,” with the voices of Drake and The Weeknd.

Opinions about the track flew fast — some thought it was a smash, or a great rough draft, while others were less sure. The difference between this track and the thousands of previous AI-voiced remixes out there is that this one used an original beat, not an existing track, and was uploaded to streaming services as opposed to simply floating on social media.

“Heart on My Sleeve,” generated 2 million + global streams according to Billboard, “worth closer to $9,400.” And then the track was taken down — not because of the use of Drake or Weeknd vocals, but because the track used an unlicensed sample. Of course, the song is still easily findable on social media. T

he whole affair has generated countless headlines, endless discussion and handwringing–and some of what I would call lazy, misleading context. Specifically — and I’ll be writing more about this on the Full Rate No Cap LinkedIn this week — can we please stop referring to this past week as “A Napster Moment”?

WHAT IS A NAPSTER MOMENT?

A Napster moment is 1999. At a time when the only way to hear hit songs in your home was to pay $20 for a CD, along came a service that offered literally every song and even every bootleg you could dream to type into a search bar, for free and without any restriction. It’s easy to say that Napster came along and offered fans everything they were paying for, suddenly for free. But for the music business, it was actually far, far worse than that. Napster was actually offering fans a substantially better experience, for free, than what they were paying for.This was true in two key ways, beyond, of course, being free. Napster unbundled albums and let fans play only the songs they wanted, on-demand. And Napster had everything, from bootlegs and B-sides to rare remixes, international versions… I mean, everything. All free. And all happening at the same time that home internet speeds and giant-capacity iPods were taking off.

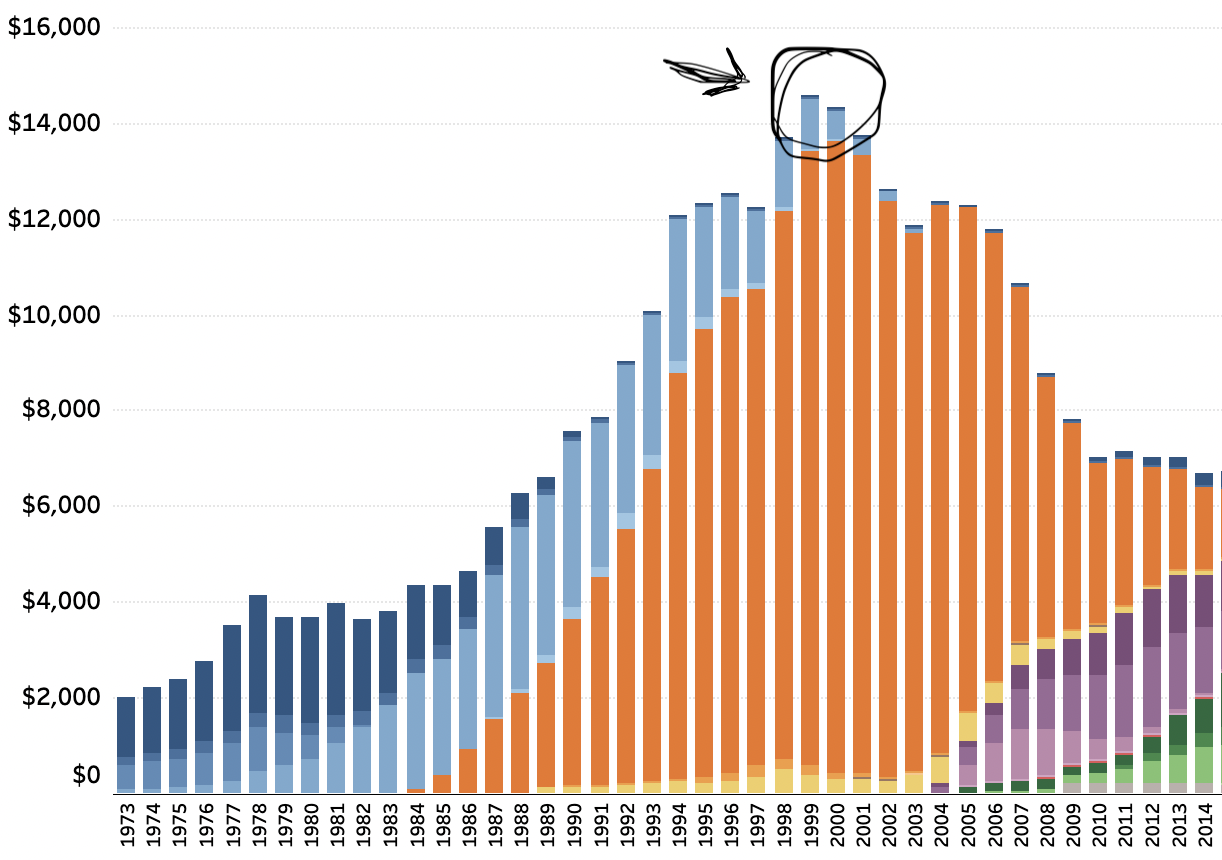

Circled is the exact time period when Napster became popular. This is what an actual Napster moment looks like.

Circled is the exact time period when Napster became popular. This is what an actual Napster moment looks like.

Napster was a giant plug pulled on the drain of the music business tub, and that giant sucking sound was half of the business’ revenues disappearing during an immediate ten-year free fall. A Napster moment was the proposition that you could take every experience you loved about listening to music and stop paying for it if you wanted to. Those of us who were around the business at that time new exactly what the Napster moment meant: it meant disaster. Decimation. This AI moment is something radically different from that.

Back then, the record business had no way of making money from file trading. Today, the record business is leaving many AI/deepfake tracks up, and collecting the royalties. Back then, the record business infamously started suing fans. It was a PR disaster, stemming from the reality that every day that went by, hundreds of millions if not billions of songs were being illegally downloaded and the record business really had no way to stop it. There is no such pressure or panic today.

This time around, existing copyright law and, potentially, artist rights of publicity are creating a very different environment — one that poses no immediate threat to the core business of music, and in fact, one that may offer plenty of potential upside. Back then, the labels inadvertently created their own file trading problem, seeding the market with billions of unprotected files (aka CDs). Today, the major labels are all invested in myriad ways in AI technologies and companies.

There are still many questions and a lot of potential risk for the music business.

Two massive legal questions we don’t yet have answers to: one, will AI trained on existing music owe the rights holders of that music some sort of royalty? And two, will rights of publicity give Drake the clear ability to issue a takedown, should he desire, next time someone decides to release a hit song with his “voice” on it. (Note: great, in-depth interview here, with IP attorney Chris Mammen, breaking down all of the legal questions raised by “Heart On My Sleeve.”) But right now, today? There may be uncertainty but no clear and immediate existential threat created by generative music.

The Grey Album

If you’re looking for a better historical reference than Napster, I’d suggest you pull the Grey Album, from that same era. The album was released in 2004 by a then-unknown producer, and mashed together and remixed Jay-Z’s Black Album with the Beatles White Album. (I think the link is subscriber-only, but I wrote about the Grey Album for The New York Times as a kid reporter.) In the early days of mass internet and social media, as well as the beginnings of increasingly affordable home-studio tools, it was mind-blowing–a critically acclaimed shot heard round the world for remix culture. Suddenly artists could interact with music and create much differently than they had, and fans could hear it, and the labels could sue but not really stop it. Any of this sounding familiar yet?

Somehow Jay-Z, the Beatles, and the rest of the record business survived. Remix culture proved to be an artistically rewarding and ultimately profitable new creative approach to music. And that unknown producer? A kid called Danger Mouse, who played his Grey Album calling cards all the way to the top of the business.