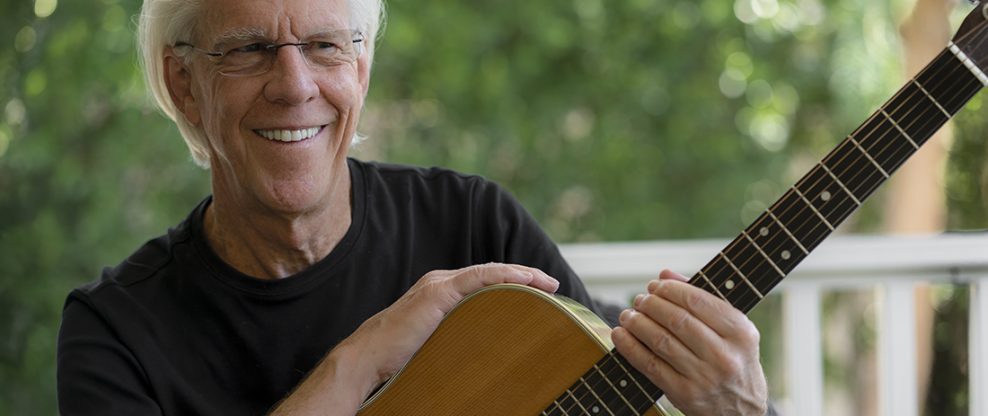

This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: Jim Ed Norman, musician/producer/arranger.

In both music and manner, Jim Ed Norman is Southern irascible, and impeccably well-connected.

Given that he is so revered throughout the music industry, his thoughts are to be listened to attentively, as his incredible wealth of musical experience as a label executive, producer, and arranger gives him wisdom that is remarkably rare.

While there are nuances to being a renowned Nashville administrative patriarch, there is little in creating musical gem after gem, and in the steering of creative talent year after year.

On the phone, the 73-year-old Fort Myers, Florida macher, following an extended victory lap leading the 60-piece orchestra and choir each night for the Eagles’ “Hotel California Tour,” is far spikier, and more complicated than expected, as he relates stories of working with the Eagles, and with other leading country and pop icons.

The Eagles picked an old friend for their tour because Norman has considerable history with the band. This includes, after meeting Don Henley at North Texas State University in the late ‘60s, the two recording together with the band Shiloh in Los Angles, and Norman arranging portions of the Eagles’ projects from their 1973 album, “Desperado” onward, including “Hotel California.”

The very first professional orchestral arrangement Norman composed was the string part for “Desperado.” Then, at 24, he was thrust onto a raised podium with a large music stand at London’s Island Records’ studio in Basing Street to conduct an undecided contingent of Britain’s best classical players.

With this pivotal credit, Norman was able to continue working with the Eagles—playing piano on “Take It To the Limit,” and “Lyin’ Eyes,” but also arranging Linda Ronstadt’s version of “Desperado,” and writing string and horn arrangements for her 1973 album, “Don’t Cry Now,” as well as overseeing arrangements for recordings by Bob Seger, America, Kim Carnes, Garth Brooks, Trisha Yearwood, and others.

Norman’s career as a producer began in the mid-1970s.

Among the artists he has produced are Jennifer Warnes, Jackie DeShannon, Anne Murray, Janie Fricke, Holly Dunn, New Riders of the Purple Sage. Kenny Rogers, Hank Williams Jr., Crystal Gayle, Glenn Frey, Michael Martin Murphey, B.J. Thomas, Victoria Shaw, Mickey Gilley, Johnny Lee, John Anderson, T.G. Sheppard, Gary Morris, Clay Walker, Pinkard & Bowden, Mac McAnally, David Loggins, South Pacific, Kathie Lee Gifford, the Forester Sisters, Tish Hinojosa, Dylan Scott, and Lee Brice.

Norman is the former president of Warner Bros. Records Nashville and former CEO of The Curb Group.

In 1983, Norman joined Warner/Reprise as VP of A&R; the next year he became executive VP, and in 1989, he was named president, a position he held until 2004.

During his time at Warner Bros. Records, Norman oversaw a roster that included Faith Hill, Randy Travis, k.d. lang, and Hank Williams Jr. while he produced Blake Shelton, Dwight Yoakam, Travis Tritt, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, Mark O’Connor, Beth Nielsen Chapman, Take 6 and others.

Norman left Warner Bros. Records in 2004 and relocated to Hawaii. There he organized a music business program partnership between the University of Hawaii and Curb College of Entertainment and Music Business at Belmont University in Nashville that had him coming back to Music City often for visits, He was also a supporter of the Music & Entertainment Learning Experience program created for the Honolulu Community College.

In 2014, Norman fully returned to Nashville, joined Curb Records as Chief Creative Officer, and went on to serve as CEO until 2019 when he started with the Eagles.

With the last domestic show in Las Vegas on May 28th, you completed 63 “Hotel California” dates overseeing a 60-piece orchestra and choir?

Yes. We did have places where we shared but, in most cases, it was with a new group of people recruited city by city. There were some exceptions. When we did Madison Square Garden in New York, and Long Island, it was the same players because we came back with COVID shutting things down over the course of 18 months shortly after getting started. We had done Atlanta, Madison Square Garden, Dallas, and Houston, and when we subsequently went back to Madison Square, more than three-quarters of the players at Madison Square were the same. When we went to Long Island, it was the same group, and when we did Washington, D.C., it was the same group.

What we were trying to do when we could was to work with local orchestras. Like when we did Tulsa, it was the Tulsa Symphony. In Nashville, the players were all people that I had worked with for years and years, and the Jubilee Singer were with us. The singers in many cases were from schools or universities when we could. In New York, we had students from The New School. Don (Henley) had this great observation for applauding the choir when they were introduced. He said, “Their grandparents were big fans of ours when they were young, you know.”

After you agreed to the “Hotel California” tour, you then had to revisit arrangements you likely hadn’t looked at in years. Your reaction may well have been, “What was I thinking back then?”

(Laughing) You are absolutely right. Although, I must say, in many cases, the things worked. The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum is doing an exhibit (“Western Edge: The Roots and Reverberations of Los Angeles Country-Rock”) that will run for three years on the history of Southern California country rock and, of course, the Eagles figure prominently into that. They got in touch with me, and said, “Jim Ed can you participate, and do you have any memorabilia?” I said, “Would you be interested in the original score of ‘Desperado?’” “And they said, “Are you kidding, yes!”

Your career as an arranger began with the recording of “Desperado” released in 1973. There you were recently on the road with the Eagles for the “Hotel California” tour, and the very last performance with the orchestra each night was “Desperado.”

So I got the original score of “Desperado,” and it has notes all through it. One says “MSG” for Madison Square Garden, and another says “Forum” for The Forum in Los Angles, and another says “Wembley” for Wembley Stadium in London. What I remember, what came flooding back to me, was that with the live dates that were done, as opposed to what was done for the record, there would be some changes in, maybe, an ending or the movement in the accompaniment of what was happening, as musician prowess grew. I might have had to along the way make changes.

In the case of “Desperado,” clearly there were changes that were made, but they were made relative to changes internally. Largely, I think the lack of my conducting experience meant that I didn’t get the most from the orchestra that was recorded. I did get to hear things now that were not as clear as on the record as they could be now in the live setting. There was an opportunity to address some of these nuances, the section that the orchestras, at any given time, needed to pay attention to.

Then we have the moment in the “Hotel California” set that is just orchestra.

It’s a signature part of the original album. if you remember, when Hotel California” first came out, it was on vinyl. Side 1 ends with “Wasted Time,” you flipped it over, and you used the orchestral reprise of “Wasted Time” to start the second side. How did that come about?

I had been so moved by “Wasted Time” that they had wanted an orchestra on that I wrote this orchestral piece. Not on assignment but because I wanted to. That day in the studio, I said, “Hey, we have a half-hour here, and it won’t cost any extra, would you like to hear this?” They said, “Of course, let’s hear what you’ve got.” Well, the records were vinyl and it opens up Side 2 of “Hotel California” with this orchestra-only piece. And it has not really changed a bit in all of the years. It is what it is because of how quickly it was done the day of the original recording. Lo and behold, as a complete surprise to me, it ended up on the record as the reprise.

With some of the others, the thing that might have changed it was the key. I play piano on “Take It To The Limit” on the record. How I got to play was that I was working for a publishing company in Los Angeles, and the guys were in town recording “One of These Nights.” Glenn Frey called me and jokingly said, “Jim Ed, I’ve been fired. I can’t play in B.” They had been trying to record “Take It To The Limit” in the key of C. (Randy) Meisener finally said, “I’m struggling trying to sing this in the key of C night after night.” So they needed to take it down a half step. So I ended up getting called in, as I did from time to time as a utility player, and “Take It To The Limit” was one of those things.

Has anyone over the years commented on the soulful elements of “Take It To The Limit?”

A fascinating thing is that Glenn and I both had a thing for the music that was being done in Philadelphia, Harold Melvin & the Bluenotes, the Gamble and Huff records, and (arranger/producer) Thom Bell. “Take It To The Limit,” for me with the orchestral, was sort of a homage to the Philadelphia music which we had been inspired by.

As I mentioned, the first professional orchestral arrangement you composed was for “Desperado.” You took three weeks to write the arrangement, and while in London with Glyn Johns producing, he said that you should conduct the orchestra being added to the track.

That must have been a daunting experience.

It was daunting. My knees were shaking. We were in the Island Record Studio. It was my first arranging experience. In Los Angeles, the guys had sent me a mix of the basic track, and I think I spent three weeks just listening to the song because I was just moved by it, and I needed to pull out what I had dreamed would support what was being said (in the song). And I had done something unusual. In an effort to have some real guts in the orchestra. I had eliminated violas. So there was kind of a skepticism as the musicians walked through the studio door, “What is going on here? We have nothing but violins, cellos, and double basses.”

Plus, you are a Yank.

Yeah, I am a Yank, and I’m a kid. I’m 24.

How was the initial meeting with producer Glyn Johns with you being so young and inexperienced as an arranger?

I think that there was bemused skepticism on his part. He was cordial. He introduced me to the contractor, and the contractor introduced me to the players as they walked in. When I went out to the recording room in the studio I noticed that the musicians did not have headphones. I said to Glyn Johns, “I notice that there are no headphones,” and he said, “You are going to conduct aren’t you mate?” And I said, “I guess that I am.”

Among the players on hand was a musician who had played cello on the Beatles’ “Yesterday,” and others that played in the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

How big was the orchestra?

I had 36 pieces. It was big, for me. It was bigger than anything I had ever seen but if I was going to do it I wanted to do I knew it was needed.

I grew up watching great conductors, whether it was Leonard Bernstein, Leopold Stokowski, or Arthur Fiedler. So I felt I knew what to do, what the motions were and keeping time, and how you conduct, and how you do that. But I had never done it. I had just seen it.

I go out into the studio, and I find myself with a group of people who are skeptical is the best way of putting it. They (the musicians) didn’t give a shit. “Who’s this joker? I’ll just play and then split.”

So we are doing the run down and the track is playing and I am the only one that can hear the track. I am conducting the orchestra. They’ve tuned up from the piano. So I am now conducting, leading them along to be in sync with the track that I am hearing, and I thinking, “Oh man, I wonder how this is going?” I’m conducting, and I look back over my shoulder and Don and Glenn Frey—the monitors are hung up on the wall and coming down into a focal point where you would be seated—they were both staring up into the speakers and they were listening intently. I’m looking thinking, “That could be taken two ways. They could really be in awe, and loving it or they could be going, “Oh my God what in the world have we gotten ourselves into?”

Don tells the story, “Jim Ed is out there, and he’s never done this before, and he’s standing up there like he knows what he’s doing.”

That night we went to dinner to celebrate. The guys had never had an orchestration on their music either. It was the first time doing anything like that. We were celebrating, and the gravity of the day hit me, overwhelms me to the point that I said, “How in the world did you talk Glyn Johns into using me?” They said, “Jim Ed, he didn’t think that you were going to be able to pull it off. He had Paul Buckmaster waiting in the wings.”

Even producer Glyn Johns was taken aback. In a 2014 interview in Uncut magazine, he said, “I didn’t realize ‘Desperado’ would turn out as well as it did, in the delivery from Henley and the string arrangement. The strings I hadn’t envisaged, I’m sure that was their idea.”

With your arranging credit on “Desperado,” you had the leverage to then do further arranging. Not only with the Eagles, but also with Linda Ronstadt, Bob Seger, America, Kim Carnes, Garth Brooks, Trisha Yearwood, and others.

It was the first arranging that I had ever done, and I owe it to Don and Glenn. They were the ones that said, “We want our guy Jim Ed to do it.”

Don and Glenn stuck up for you.

The thing that I’ve always appreciated was that first and foremost the guys gave me my break, stood up for me, and said, “This is who we want.” There was this skepticism, if not downright cynicism over “What in the world is going on here?” because it was so unusual.

In a Stanford University commencement address in 2005, the late Steve Jobs, then CEO of Apple Computer, and of Pixar Animation Studios, said: “Of course, it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backward 10 years later. Again, you can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.”

His point being that you only can evaluate what you’ve done later in your life. As you are experiencing your career and life, the connections aren’t as apparent. You do what you do. You aren’t reflective. Decades later, you look back, and consider, “How did I do all those things?”

I look at your career and I think, “When did Jim Ed ever sleep?”

I am known for being able to get by on very little sleep at least at that point in my life. I’m trying now to get better about it. I still, unfortunately, live that way. I don’t know if it’s a good, healthy way to live as far as no sleep. I think that there’s just a sense of early understanding that your job as a producer is to hire the best person for the job. You had a role. You had a responsibility, but it didn’t mean that you had to do everything. I was able to surround myself with wonderful people. We had a good process going on as far as how we would communicate; how we would undertake work, and to do things. And it did lead to a period of great output. But I think that is just what happens, you know. You are younger. Your life is focused on that, to the peril of other parts of your life, unfortunately.

You will have a broken marriage in there somewhere.

Yeah. Well, that’s what happened. But you just don’t see it coming. You don’t understand it because you are consumed with this sense of mission on one hand, and accomplishment on the other. I remember one time the (Warner Bros.) CFO out in Burbank saying, “Hey Jim Ed are you coming out to the Grammys this year? You’ve got a lot of nominations.” I said, “No, I’m busy working on next year’s nominations.” I didn’t even stop to revel in what had happened.

I think what largely drives creatives are deadlines.

That is a significant part of it for sure. “I’ve got to get this done,” so you go on and you make it happen. You’re right. Being in the studio with the New Riders of the Purple Sage, up in Sausalito (at the Record Plant) when they had to leave to go on a European tour, we had about three days to get about six days worth of work done. I remember putting the guys on six-hour work increments as I was overdubbing. The tracks had been cut, and I needed each one of them individually for various things. And Tom Flye, a wonderful, wonderful engineer, and person too, a wonderful, gentle man, I remember he and I kept going for three days straight just on coffee. We didn’t stop. We just kept going with a combination of adrenaline and coffee. Occasionally, we grabbed an 8 or 10-minute nap or snooze. Just being a tag team to keep going.

You are right. Those deadlines are where you had to get stuff finished because so many people depend on it.

I remember one time with an artist, who will remain nameless, who came in, and said, “I’ve decided I am going to take a break.” I said, “Okay, what do you mean?” He said, “I’m going to take off a couple of years.” I was young and new in running the record company, and I said, “Hey, let’s talk about this for a minute. You realize that you have built a partnership of people here, and in this partnership that has been built, it is about what you do, what you know how to do best, and they all do what they know what to do best? In that partnership, a team comes together in order to keep things going. I only have one thing to say. I hope we are still in business and here when you decide to turn in your record.” To which he said, “Okay I understand. I’ll get busy.”

So he didn’t take two years off, and oddly enough I think it’s his best work, or the closest to it, that got turned in.

You can be too much of a taskmaster too. I was doing a session in Los Angeles once, and I was young, and just getting started as a producer, and we started at 10 o’clock in the morning, and I think it was about nine o’clock at night, and we’d taken breaks for the guys to go grab lunch. To get something to eat for dinner, and then they came back.

So we were closing in on 12 hours.

All of a sudden one of the guys says, “Jim Ed, I have to fix something here on my gear.” I said, “Okay.” So I’m talking to the rest of the guys about things that I wanted to change on the arrangement that we were working on. All of a sudden, I said, “Let’s count it down. Let’s go.” And there’s nothing. And there’s nothing again. I see that a couple of the guys have their heads down, and are not looking at me in the control room. I go out into the studio, and one of them had gotten down on their hands and knees, and slipped out the back door.

I then realized that people who do this for a living knew more about the general kind of feeling and consciousness that can be going on with a group of people on what you are trying to accomplish than what I did.

My point is that I got some great lessons along the way and that the door always swung both ways.

This time I was learning, and then there were times when I was trying to impress upon an artist or someone the idea that this is one big family, and that this is a team of people who work together. But you really do need to be responsive to deadlines and pay attention to what is happening. Occasionally, deadlines can slide. I know that there have been great expectations from record companies from time to time about when the Eagles’ new album will be turned in.

In 2016, you were presented with the Bob Kingsley Living Legend Award, and Big & Rich, Don Henley, Mickey Gilley, Michael Martin Murphy, T.G. Sheppard, Gary Morris, Crystal Gayle, Lee Brice, Mo Pitney, Jeff Hanna, and Kenny Rogers turned up to pay tribute to you. And Randy Travis made an unannounced rare public appearance.

In his speech, John Rich said, “Jim Ed, you’re the reason everyone knows about us, so God bless you.”

I’m sure you have never dwelled on this but, by signing or working as a producer and label executive with some of the artists that you have, you may have changed a number of these peoples’ lives. Do you ever reflect, “Wow, this person may not have made it without me signing or working with them?”

No. No, I don’t. I’m thrilled to have gotten the opportunity on my side. I feel like they changed my life as much as anything that I did. Occasionally, an artist will say, “You made whatever…” and I have been instructed repeatedly by those around me, and who love me, and care about me, “Can’t you just say ‘Thank you?’” I’m working hard now on just saying “Thank you.” What I am so desperate to say is, “No, no, no, you don’t understand. That was who we were as a team, and what we did together.” When I signed Take 6, people have said, “That was really taking a chance.” It was the easiest thing I ever did in my life. A genius? I don’t think of it in those terms. I am always especially impressed and thrilled when someone who has been given an opportunity makes the most of it, and then gives back, and does the same thing with others. If I ever allow myself a moment to go, “Well, I really changed their lives…..” What I have been able to say, and recognize is “Look at how this person has changed other peoples’ lives. How they have passed on whatever opportunity that came to them to others.”

You said something very significant onstage at The Grand Ole Opry House when you were presented with that Bob Kingsley Living Legend Award.

You said, “The Opry is a place that is safe. People come back here to exchange ideas, build relationships. New artists come here, see how things are done, see legends and be inspired.”

The Grand Ole Opry has been hailed as the “Home of American Music,” and “America’s most famous stage.” When you think about the size of Nashville, and realize that for over 96 years the Opry has witnessed country music’s biggest moments including Bill Monroe inventing bluegrass on the Opry stage, or Johnny Cash meeting June Carter at the Opry.

I said that as a sense of appreciation of the Opry. I had been snookered that evening in showing up for Pete Fisher (the VP & GM of the Grand Ole Opry) to speak on the role that the Opry plays in the development of an artist. I said to Pete, “You know how I hate to do anything on camera. I hate that. I’ve spent all of my life trying to be behind the scenes, and push other people out front.” He said, “I know, but would you do this for me?” I said, “Okay.” And I come out, and it turns out to be about the Bob Kingsley Living Legend Award. I’d been completely snookered. And, in that moment, I do realize in receiving that award that I am appreciative because the award was connected to the Opry Trust Fund that helps support artists who have given so much to country music, and to the history of country music.

So, you didn’t know that you were receiving the Bob Kingsley Living Legend Award which is named after radio personality Bob Kingsley, best known as the host of the nationally syndicated radio programs, “American Country Countdown,” and “Bob Kingsley’s Country Top 40?”

No. I was told, “We are doing a TV special about the role the Opry plays in the development of an artist. “ I was like, “Okay, I’ll come.” And I tried to get the sound bite consciousness going because I start being a preacher a bit at times. So I did not know. When I checked in, Pete came out from the backdoor, and said “Come in, and you can wait in here.” I went in there still not knowing what was going on. I saw Bob Kingsley, and his wife Nan, and I thought, “ Of course, it makes sense to have Bob. As a historian, he would be a part of this as well.

Then someone said to you, “Jim Ed, we lied to you.”

I said, “Okay, this is the music business, why should tonight be any different?” I was told, “There are a number of people who have turned up tonight to fête, and to recognize the contribution that you have made. Bob Kingsley got the first award, and then (Joe) Galante (eventually the chairman of Sony Music Nashville), and this year it’s you, and you are there.”

Talk about a hot seat, Larry.

There was parade of people who sang. It was a wonderful evening. I was thrilled that anything that I would do would recognize those having made a contribution to the industry, that the proceeds would go to something like that because I do think that the Opry—you have someone like Vince Gill who goes back and plays the Opry, and is there and is accessible with his door open. Young artists are able to see how people operate, how they work, the accessibility of artists if they have questions.

So, it is a great learning place.

The Ryman is the Mother Church, but it is also a place of great inspiration, whether it (a show) is done at the Ryman or out at The Opry House, it embodies the same kind of character. The band that plays, and the artists that do their relatively brief segments, are a stellar group of not only musicians but people. People who have been part of the industry for a long time. Anyone who passes through, and watches what is going on, will be impacted. Talk about getting a Ph.D. At least, you are getting your Master’s in life. What this is about is family. It is a great environment to experience the full breadth of possibilities if you will.

In the mid-’70s, while working with Canadian actor Don Harron on the TV show “Hee Haw” (on which he played his signature KORN newscaster character Charlie Farquharso), I spent considerable time at The Grand Ole Opry House, including with Cousin Minnie Pearl, the wisecracking backwoods Queen of Country Comedy who, as we all know, wore a flowered straw hat with its $1.98 price tag attached, and a thrift-shop cotton-print dress.

I taped Minnie and Don reciting a scene from William Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” consisting of the subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta.

Minnie was culturally refined.

Later, I discovered that her mother Fannie House Colley, the epitome of genteel Southern womanhood, and also one of the social leaders of Centerville, Tennessee, was an accomplished pianist who supplied the background music for recitals, plays, and musicals at the local opera house.

So, Minnie Pearl was raised in high style.

She went to Belmont University.

She graduated from Nashville’s Belmont University when it was still Ward-Belmont College, a prestigious women’s college, located on the grounds of the former Acklen estate. It was then a “finishing school” for the more aristocratic families of Middle Tennessee, Minnie was fixated by its drama department and its director Pauline Sherwood Thompson, After graduation, she taught dance before being hired as a drama coach for an Atlanta theatrical agency that presented shows in rural Southern towns.

Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon…

Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon. She was one of the sweetest people that I have ever met, and so kind. When I first moved to Nashville there was some difference of opinion about whether or not I was a good addition to Nashville because I had come from Los Angeles.

After producer Jimmy Bowen moved to Nashville from Los Angeles in 1977 he said, “I had flown into Nashville often to find songs, but I found Nashville more welcoming then if you were a visitor. If you moved here, you were a carpetbagger.”

I’ve never been a memorabilia collector, but I have saved a few things through my experience in life that have been particularly touching and meaningful to me. One of them is from Minnie Cannon, from Minnie Pearl. It was a note saying, “Welcome to Nashville. We are thrilled to have you here, and we look forward to great things.” It was just a beautiful note of acceptance, and it resonated with me, and it meant so much because of who she was, and the contributions that she had made.

Minnie talked to Don Harron and me about “double comedy” which she and Rod Brasfield perfected when they formed a double act in 1948 in which each of them delivered alternating punch lines, and neither played the straight man. With his trademark baggy suit, battered hat, and rubbery face, Rod who had joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1944, could make audiences laugh before he spoke a word.

Minnie Pearl, while being a raucously funny radio, television and stage personality, her comedy was as sophisticated as any comedian. She was on the comedic level of Lucille Ball.

Absolutely. You obviously know (Belmont University professor and music historian) Don Cusic. He has done a play (“Minnie Pearl: All The News From Grinder’s Switch”) about Minnie’s life.

“Minnie Pearl: All The News From Grinder’s Switch” made its debut this weekend at Nashville’s Chaffin’s Barn Dinner Theatre in a very limited, four-performance engagement in September 2019.

Writes Don Cusic: “I’d love to revive the Minnie Pearl musical–it was scheduled for a second run in April 2020–just before the country shut down. Alas, I’ve had to put that project on “hold” for now while I finish up some other projects.”

Nashville’s fabled Music Row, a rectangle between 16th and 17th Avenues South, and Division and Grand Streets, extended the commercial reach, and popularity of country music, beyond the barn-dance ethos of the Grand Ole Opry. But the city itself had an uneasy relationship with the country music community as the genre eventually morphed into a commercial industry.

Nashville administrators prefer the descriptive tagline, “The Athens of the South,” a backward glance to when Nashville was one of the most refined and educated cities of the South, filled with wealth and culture.

At its center were the city’s schools, including Vanderbilt University, Fisk University, the Ward-Belmont School, David Lipscomb College, Meharry Medical College, Roger Williams University, Peabody College, St. Cecilia Academy, Montgomery Bell Academy, and Tennessee State University, all combining to emphasize Nashville’s distinctiveness as a regional center of learning.

That’s it. “The Athens of the South.”

Not only did Nashville administrators keep a tight rein on the growth of Music Row, they ensured that the 4,000-seat Grand Ole Opry House, which opened in 1974, was built outside of its then city limits.

National Life & Accident purchased farmland owned by the Rudy’s Farm sausage manufacturer in the Pennington Bend area, 9 miles east of downtown, and adjacent to the newly constructed Briley Parkway. The new Opry venue included the Opryland USA Theme Park, and the Opryland Hotel.

While Nashville has long been identified as a country music town, it has always had a lively rock club culture.

It has. Jimi Hendrix was down on Jefferson Street at one point in his development. So it has always been a mix (of musics). It was “Music City,” and it was thought of being country music historically during my formative period at Warner Bros.

Jimi Hendrix moved to Nashville in 1962, and began performing locally on a regular basis billed as “Jimmy Hendrix and his Magic Guitar.” His first known TV appearance was as a backup musician on WLAC Channel 5’s “Night Train” show hosted by Noble Blackwell. Hendrix and army buddy Billy Cox formed the King Kasuals which served as the house band at the Club Del Morocco on Nashville’s Jefferson Street. Hendrix and Cox, living together on Jefferson Street, above a beauty shop called Joyce’s House of Glamour, were also regular players in Printers Alley. In recognition of his stay in Nashville, Hendrix was Inducted to the Music City Walk of Fame in 2007.

They also call Nashville the “Buckle On The Bible Belt” because It is the religious printing and publishing capital of America with the printing of bibles, hymnals, Sunday school books, scripture tracts and religious magazines.

Nashville is the home of Thomas Nelson Publishers, reportedly the biggest Bible publishing company; United Methodist Publishing House, the largest church-owned and operated publishing, and printing plant in the world; and Gideons International, the world’s largest Bible distributor, is also headquartered there.

And that is just the tip of the iceberg. Health care, for sure, is a core Nashville business with more than half of the privately-owned hospital beds in America being operated by Nashville area companies.

Yeah, insurance and health care are a major part of Nashville today.

By the way, I have a copy of the “Shiloh” album on Amos Records that you recorded with Don Henley in 1970.

Oh, for goodness sake.

What were you studying at North Texas State University when you two met earlier?

I think it was for a Bachelor of Music Education degree. To be a music teacher, I guess. At this point, I was really uncertain. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and what made sense to do. You had to declare something.

I didn’t graduate. I left after two years to go to Los Angeles.

Growing up in Florida you had a deep interest in music.

As a kid, I grew up attracted, and listening to music, and then I began to play, and learn instruments in the 5th grade. The first instrument I played was the trumpet because my father had been a trumpet player, and he had one. So I started with trumpet. It took me on the path of largely instrumental music. Not fully, maybe, appreciating yet the value of a lyric in creating a full song. I was swept away by the potential of instrumental music, and what orchestral music is. Even today it can raise the hair on my neck, just as well as, maybe, a beautiful lyric.

Did your interest then include big band and swing music?

Well, that is what I was going to say. That is how I was able to continue on because I was going to school in Florida, and I had gone through a number of instruments, and changed, and changed, and changed; learning how to play a lot of instruments a little bit. Some more proficiently than others. The instrument that I was playing in the later years of high school, as a senior, was trombone. I was also the bass player because I had proposed to the band director of the school, “Can we start a jazz or dance band? “And he said, “I’d love to, but we don’t have a bass player.” I said, “If you get one, I will learn how to play it.” So picture me playing in the band there with the upright bass. But I was a trombone player. I went on to my first couple of years in college, and I was playing trombone in this big band. At the time the big band school was really North Texas State University in Denton, north of Dallas. So I went to North Texas.

At North Texas State University, your name changed from Ed to Jim Ed. How did that happen?

A fellow came back from being in the Navy, and he also went to North State, and because there was now another Ed right next to me in the trombone section, there was a concern that confusion would happen. I was told, “This comes to an end right now. We are going to change your name from Ed to Jim Ed after Jim Ed Brown (of the country trio, the Browns) because you like country music.” So they were kind of giving me a dig (because of being a country music fan), but I wore the name proudly, and I became Jim Ed. They had computer readouts for classes that you signed up for, and I was on the sheets as Edward James Norman. And, all of a sudden, I was getting called Ed or Edward. I had never been called Ed or Edward in my life. I had always been called Jim. But who cares, Edward Norman or Jim Ed?

Where did your interest in country music come from?

I had grown up around country music because of relatives. My father was a minister. I heard a full complement of every music that you could hear but, in particular, I liked country music. I would ride with him in the summers from mid-state Florida, from around a town called Cocoa. We would get in his pickup truck with Skip the German shepherd riding in the back, and we would ride all the way to the extreme of north Georgia in the mountains to Hiawassee, Georgia, where my uncle and aunt had a summer house that they had built. We would spend the summers there, and we would listen to country music all the way there, and I became a fan.

In those early days too, when I was growing up, a lot of country music crossed over into pop. The Nashville Sound was a significant part of country music crossing into pop with (producer) Owen Bradley. The great orchestral arrangements, and the general character of the music was very appealing and, in many respects, not dissimilar to the things that I was appreciating in pop which was a band of musicians, singers, and in many cases an accompaniment of just that band and singer and having orchestration of some sorts.

In the ‘50s and early ‘60s there wasn’t a specific demarcation of what was country and what was pop. Patti Page singing “Tennessee Waltz” or “Cross Over The Bridge” wasn’t unlike what Patsy Cline, Teresa Brewer, Jo Stafford, or Georgia Gibb were also doing in that she blended country music styles into many of her songs, resulting in many of her singles appearing on pop and country charts. Hank Williams was more pop than say Ernest Tubb or Hankshaw Hawkins.

I would listen to all kinds of music. I would go to record stores, and flip through records. I would buy and just listen.

What was great about that era was that transistor radio receivers picked up “skip” broadcasts at night from cities hundreds of miles away. We could hear The Big 8 CKLW, the 50,000 watt powerhouse AM station from Windsor, or WINS in New York, or WLS in Chicago and, of course, “John R.” (John Richbourg) on WLAC in Nashville. The airways spilled over with Top 40, R&B soul, jazz, and big band.

With CKLW, I really got into R&B soul music. I grew up in Florida but, as you said, with that 50,000 watt “skip” that would happen, you could pick it up on occasion on specific nights. The music that I heard was really appealing and attractive because it was an adventure for me. I was hearing a lot of pop music when I listened to the radio but some of these things I would have to go on a hunt for

I was truly into the Dillards, and I happened to be walking down the apartment complex one day, and Don (Henley) was playing Led Zeppelin with his door open. I grabbed my Dillards’ record, and I said, “You have to check this out.”

The Dillards were pretty advanced progressive bluegrass for that time. They were among the first bluegrass groups to have electrified their instruments in the mid-1960s.

Yeah, I guess. They were considered the first progressive bluegrass band. Of course, I knew the Dillards because they were the Darling family on TV.

Brothers Doug and Rodney Dillard played members of a family band, the Darlings, making just 6 appearances on “The Andy Griffith Show” between 1963 and 1966. Joined by their jug-playing patriarch Briscoe Darling (actor Denver Pyle) and sister, Charlene (actress Maggie Peterson), the Darlings introduced bluegrass to many Americans.

Things then were beginning to grow and develop. I came across the Dillards also because of my inquisitive nature, knowing about Elektra Records’ Jac Holzman ( founder, chief executive officer, and head of Elektra).

Elektra Records’ sixth released album in 1963 was the Dillards’ “Back Porch Bluegrass” album which helped to establish the group as one of America’s leading traditional acts. It was followed by “Live!!!! Almost!!!” (1964) the instrumental “Pickin’ and Fiddlin’” album (1965), “Wheatstraw Suite” (1968), and “Copperfields” (1970.)

By founding a compelling variant of bluegrass, the Dillards were a driving force in modernizing and popularizing the sound of bluegrass in the 1960s and ‘70s.

In this period, which was around 1968 when I went to North Texas playing in the big band, it was a period in which jazz was the highest of the high art forms, and country was the lowest of the low. I took great umbrage with that. Buddy Rich would get on “The Mike Douglas Show,” and he would just lash out country music. I would think, “Oh, my goodness.”

In 1971, jazz drummer Buddy Rich on “The Mike Douglas Show” stated that he couldn’t stand country music. He said, “I think it’s about time that this country grew up in its musical taste rather than making the giant step backwards which country music is doing. We try very hard to do things like the moon landing and our new cars and fashions and everything All a step forward and country music is a giant step backward. It’s so simple that anybody can sing it, anybody can do it, anybody can play it on one string. I think it’s about time that we learned that there has to be a higher degree of musical intelligence and we have to start to listen to better things rather than to the simple things.”

Back then, Frank Sinatra continually took swipes at pop music. Conversely, Leonard Bernstein, the director of the New York Philharmonic, was among the first American classical musicians to publicly recognize the artistic worth of the new wave of pop music.

Bernstein hosted “Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution,” the 1967 TV documentary which was a defining cultural moment in America. The program had contributions by Frank Zappa, Graham Nash, Tim Buckley, Herman’s Hermits, Roger McGuinn, Graham Gouldman, and a remarkable performance of Brian Wilson performing “Surf’s Up,” and a 15-year-old Janis Ian performing “Society’s Child,” then a highly controversial song about interracial romance.

Bernstein’s championing of pop music on TV was pivotal.

Right with his Young People’s Concerts.

It was Kenny Rogers who got you to L.A. to work with Don Henley?

It was.

The big deals in Texas in those days was Kenny being with the First Edition. and his older brother Lelan, best remembered as a pioneer of rock music in Texas. He signed and produced the 13th Floor Elevators, the Red Crayola, Bubble Puppy, the Golden Dawn, Lightin’ Hopkins, Mickey Gilley, and Esther Phillips.

Yeah, that’s right. Kenny had the First Edition by then in the late ‘60s. I had gone back to Florida, and I was working at Cape Kennedy in ’69 on Apollo 11. I was a gopher but I was there working the first time that we went to the moon. Then I went back to North Texas in the Fall (of 1970). I had stayed in touch with Don, and he called. What had happened was that one of the guys (Jerry Surratt) in Don’s band was tragically killed in a motorcycle accident. He was the keyboard player, This was before Shiloh. So Don called, and he said, “Jim Ed you have similar tastes and interests in what we are doing, and where we are heading.” At the time, it was just a four-piece band. They didn’t even know if they were going to continue on. They asked if I would be interested in being in their band. I had played in bands in Florida as a kid, starting with a folk trio, and I had worked my way through other bands.

Staying at North Texas State University in order to graduate didn’t appeal to you?

At this point, I had come to grips with the fact that I was not going to be a teacher. I was not cut out to be an academic. My brain didn’t work that way. I flunked everything. I couldn’t manage. The name that they have for it now is ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), Larry.

After the motorcycle accident, Don and the remaining members had regrouped, joined by you as their keyboardist, and with steel guitar player Al Perkins. This lineup of Shiloh recorded the self-titled “Shiloh” album on Amos Records in 1970, with Kenny Rogers producing.

Amos Records was run by Jimmy Bowen.

That’s correct. It was at Amos with Shiloh where I met Jimmy.

The “Shiloh” album has been out of print for decades. Its label, Amos Records, went out of business in 1971, and the album has never received an American reissue. However, it was released on CD in South Korea in 2014 by the Big Pink label.

Outspoken and witty, Jimmy Bowen was one of the towering figures in American music for several decades, and he would become a constant throughout your life as producer and executive with labels that included Reprise, MGM, MCA Nashville, Elektra/Asylum, Warner Bros., Universal, and Capitol.

In the late ‘50s, the late 1950s, Jimmy Bowen had the bass player and singer for the rockabilly band Buddy Knox & the Rhythm Orchids, which scored a #1 pop hit in 1957 with “Party Doll” (sung by Knox) backed with “I’m Stickin’ with You” (reaching #14), issued under Jimmy’s name.

While heading Amos Records in L.A. Jimmy recorded Bing Crosby, Mel Carter, Frankie Laine, Johnny Tillotson, Frankie Avalon, The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band, and Longbranch Pennywhistle which included Glenn Frey and J.D. Souther.

Jimmy Bowen moved to Nashville from Los Angeles in 1977 after producing Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Kenny Rogers, Glen Campbell, and Sammy Davis, Jr. Bowen got into country first in 1975 from the West Coast, signing to MGM Records adman Bill Fries, who was masquerading as a trucker named C.W. McCall. The result was the #1 pop hit “Convoy.” Bowen went to produce Conway Twitty, Garth Brooks, Hank Williams, Jr., Reba McEntire, the Oak Ridge Boys, George Strait, Suzy Bogguss, Kim Carnes, and many others.

What are your memories of Jimmy?

Jimmy, he was great. The sense of confidence that he had was unparalleled about anything that he tackled. He had been A&R at Warners in L.A. in the early ‘60s, and as a producer, he was working with Frank Sinatra, and Dean Martin, and all of these people he was producing, and he’s having to manage big sessions and all of the things that went on. He had a good song sense. He just knew how to manage creative people successfully.

How I ended up moving to Nashville was frankly two-part. One part was I had two small children, two small girls, and I had decided at this point I needed a change in my career. I had a company in L.A. and a company in Nashville for independent production, and publishing companies that had been an outgrowth of my working with Anne (Murray), and the success that had come from that. But I’d get questions from artists like, “What do you think of my records? What do you think of my manager? What do you think of my album cover?” I realized that I made records, and turned them into the company, but I didn’t know what a record company did. And I needed to learn so I could then provide some real honest responses, and counsel rather than making things up.

So I called Jimmy who was in Nashville, and I said, “Can you put in a word for me at Elektra in L.A. I’m going to apply for an A&R gig there. I want to work for a company for a while, and understand the mechanics, and what happens.” He said sure that he would do that. And he turns it in, and within a month or so of me figuring out how I wanted to apply for a position, the decision was made that we would move to Nashville for the sake of the children, as much as anything. Just a different environment for them to grow up in. I called Jimmy, and I said, “Thank you so much,” and he said, “Why don’t you come and work with me? I will help you with the business and how it operates. I am planning on retiring here.”

Was Jimmy then at Warner Bros. Nashville?

Well, he was at Elektra at the beginning of our conversations, and during this period there was an exchange between Elektra and Warner Bros. with Bob Krasnow and Mo Ostin where Mo (at Warner) gave up some of his R&B artists because Krasnow (at Elektra) was a real R&B aficionado, and he wasn’t a big country fan at the time. The exchange was that Elektra’s country catalog and country artists signed to the label would become Warner Bros., and some R&B artists from Warner Bros. would go to Krasnow who was operating Elektra largely out of New York at the time.

In that conversation I was having with Jimmy about coming to work for him in Nashville, it became Warner Bros, and the idea was that he would retire in 5 years or whatever, and he would teach me the business during that period. Well, he left 7 months later and, as fate would have it, Mo Ostin was a big fan of A&R people, music people, and producers–he had Lenny Waronker, Russ Titelman, Ted Templeman, great creative people, and producers working for him there at Warners (in Los Angeles). So he had a degree of competence for sure, and he gave me the opportunity to start 7 months into my role at Warners and be responsible for the Nashville division.

A handful of people in Nashville have been both on the business and creative side of the music business. Starting back with Don Law Sr., Owen Bradley, Chet Atkins, Billy Sherrill, Bob Ferguson, Fred Foster, and Jack Clement on to Jimmy Bowen, Allen Reynolds, Jerry Crutchfield, Joe Galante, Tony Brown, Tim DuBois, James Stroud, and Scott Hendricks.

These are multiple roles in which an executive spends hours of time in the studio overseeing sessions and bonding with artists and musicians, but then, as a corporate executive often pondering, “Do I keep this artist on the roster?”

At the same time, as you arrived in Nashville Jimmy was in the midst of leading an campaign for increased pay for studio musicians, and he was lobbying to increase label budgets for country music albums, most of which were then being produced with $15,000 budgets while pop and rock albums were apt to receive 10 times that.

Plus for most of the studios in Nashville, the transformation from analog to digital recording—a standard in the industry–hadn’t quite happened, but there was momentum to do so.

A lot of that back then was changing, as you were saying, including technologically, but also because the impact that the music was truly having on the market was beginning to be recognized. All of sudden, we had a breakthrough at Warners where we were fortunate to have Randy Travis, Dwight Yoakam, and Faith Hill. We got into the comedy business with Jeff Foxworthy. Then with my interest in different music, we ended up with Take 6, Béla Fleck and the Flecktones, and Mark O’Connor.

During your time at Warner Bros., you formed a gospel label, Warner Alliance, and Warner Western for Western-themed music. You signed and produced Take 6, and Beth Nielsen Chapman.

It was an effort to recognize the full complement of music that was going on In Nashville. I always joked with Mo (Ostin) that, “You sent me down to run the country division of Warners, and my first goal was to change it to be referred to as the Nashville Division of Warner Bros., and then the longer goal for me was to become the South Eastern Division of Warner Bros.

In 2004, you relocated to Hawaii for a decade, and when you returned you became a part of the production team behind Dylan Scott, including co-producing his 2013 debut single, “Makin’ This Boy Go Crazy, which spent 10 weeks on the Billboard Country Airplay chart. You also co-produced his #1 Country Airplay hit “My Girl,” and such follow-up singles as “Hooked,” “Nothing to Do Town,” “Nobody,” and, “New Truck” which reached #8 on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart.

How did you come to work with Dylan Scott?

While living in Hawaii, prior to my full return, I got an email with a song attached from Doug Johnson who was head of A&R for Curb at the time. He asked if I was interested in co-producing with him, and, when hearing Dylan’s voice, I immediately said “Absolutely yes.” I loved what I was hearing, and was excited at the prospects of what could be achieved. I couldn’t start for a couple of months, and the artist wanted to wait. It turned out his father was a big Eagles fan. Doug subsequently left Curb but I continued to work with this young man, and proud to say that after several years of focused development we had our first #1 record “My Girl.” which went #1 in 2016, and that was rewarding because I had been working with Dylan for several years. That first one was the most rewarding and, for any of subsequent ones to be successful, to come to radio and be heard, has been very rewarding.

I continued to work with Dylan until my departure for the Eagles.

Having #1s with a newer artist must be a great moment of triumph.

I think that for me it has always been a series of…when something is accomplished for the first time, it really resonates with me. The first time I did an orchestral arrangement that was on the radio. The first time I played piano on something that was on the radio. The first time that I got #1, I retain all that.

How about winning your first Grammy in 2021 for your work on the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ “Celebrating Fisk!” album? And having it with the African-American a cappella ensemble at Fisk University organized in 1871 to tour and raise funds for college?

No question, it was highly rewarding to be connected with that.

You are the founding president of Leadership Music, a Nashville-based organization that brings together music industry personnel, encouraging community spirit, education, the cross-pollination of ideas, and issue-based interaction.

I think it falls upon us to ensure that what we do gets passed on.

Absolutely. I agree. And that I have had the opportunity to do that at a collegiate level has been important to me. In respect to Leadership Music, in having moved from Los Angeles to Nashville, I realized the change that Nashville was undergoing. It was getting ready to explode. Nashville had carried the reputation for the longest time that, “In Nashville, everybody knows everybody. Everybody are best friends.” And I learned quickly that was not the case. Not only were they not necessarily best friends, but they didn’t even know each other. And yet, we all depend on each others’ businesses to make ours work. Whatever the particular area of the business is we depend on all of these other people, and we know so little about their business, really. We have not developed an appreciation for each others’ businesses and for what we each do to contribute to this entire industry. And out of that came the notion of Leadership Music. Calling a group of people together to say we ought to provide some kind of environment where people can learn about other peoples’ businesses, learn the breadth of the businesses, and create a mechanism that can change with the changing business.

You were also the original fundraising chair and past president of the W.O. Smith Nashville Community Music School which provides private music instruction for the children of low-income families.

The W.O. Smith School is another wonderful experience for me. When any young person gets this opportunity to go through that program and ends up with a scholarship to the Oberlin Community Music School it is just an exquisite moment for me in realizing the contribution that a program like this makes to people who have a dream, and an aspiration to do something in music.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is a co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.