This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: John Titta, Executive Vice President, Membership, ASCAP.

John Titta is unquestionably a major figure in our musical life and, perhaps, in the history of American music.

He is executive vice president, membership, of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), a post separate from, but very much complementary, to his previous role as a renowned music publisher.

Titta, who joined ASCAP in 2013, is the confidant and adviser to the performing rights organization’s writers, composers, and publishers in all genres of music, including pop, rock, country, hip-hop, R&B, Latin, symphonic, classical, film and TV music, and musical theatre.

From New York City, he oversees a national team of membership representatives who are based in Los Angeles, New York, Nashville, Atlanta, Miami, San Juan, and London.

Not only does Titta get to work with multiple genres of music, and with songwriters at every level of their careers—helping them get to the next level–but he also has firm ties with many of the world’s most celebrated songwriters. He’s available to help to make new connections and to annually honor them.

The long game for Titta is his determination to elevate the profession of songwriting so that the world understands the importance of music and its creators.

ASCAP is a professional membership organization of songwriters, composers and music publishers of every kind of music. ASCAP’s mission is to license and promote the music of its members and foreign affiliates, obtain fair compensation for the public performance of their works, and to distribute the royalties that it collects based upon those performances.

With more than 750,000 members representing more than 11.5 million copyrighted works, ASCAP is a worldwide leader in performance royalties, service, and advocacy for songwriters and composers, and the only American performing rights organization (PRO) owned and governed by its writer and publisher members. Its Board of Directors consists of songwriters, composers, and publishers.

Titta presents two distinct faces at music conferences and award shows. The one he wears most often in public is that of a cherubic, humble man who smiles often, speaks softly, and who cultivates the virtues of civility; striking those who meet him as being incredibly thoughtful, and above all, a truly passionate music fan.

The other face is that of a deft, and forceful administrator who pushes hard for songwriters, and for songs.Someone very influential in the acquisition and retention of many prominent ASCAP members, and in the development of originative business practices; instrumental in the programming of workshops, song camps, award shows, and such events as the highly successful, three-day annual ASCAP “I Create Music” EXPO, rebranded as The ASCAP Experience last year.

The two sides of his personality and character is of a complex man. His kindliness and good humor are as genuine, as his ambition and velvet-gloved toughness.

From Staten Island, New York Titta’s first job in music was as a certified music teacher in New York’s public school system, and a private instructor. In time he decided to become a professional musician and soon started being hired as a session player. As a result, he began writing songs with songwriters signed to Screen Gems/EMI Music where he was soon hired to work in the tape room.

When he entered this world, New York was the richest music publishing concern in the world. Access to music publishers of prominence was open to him. New York is also America’s financial center, and the world’s media capital and the front doors of the music industry opened into the heart of it. Being a music publisher or song plugger was a job made for someone as personable and music-savvy as Titta

It’s unsurprising that over the next two decades he had outstanding success after success in finding emerging songwriters, in getting cuts, and in negotiating commanding publishing deals.

After four years at Screen Gems/EMI Music where he became a professional manager, Titta next moved to PolyGram Music Publishing as vice president of A&R in 1988 for five years; and from 1993–2006, he served as senior vice president/general manager of Warner/Chappell Music in New York.

Prior to joining ASCAP, he ran his own firm, MPCA Music Publishing.

Titta proudly serves today on the Board of Directors for the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

We’ve all see those photos of you in the trades over the years with music icons and up-and-coming songwriters. You have had a catbird seat for witnessing America’s music culture in all genres for our times. That’s a hell of a place to be.

Well, I think I just have an awareness of what’s going on. I have a photo with Cab Calloway taken in 1986, I guess. Even as a kid, I met Gene Krupa, and I got his autograph. There are photos I can’t find anymore that are amazing. I know that I have one of me, George, and Ringo at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I don’t know where it is.

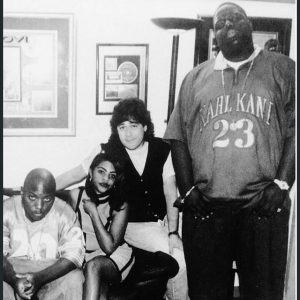

Tell me about the photo taken in your old Warner/Chappell office of you and Biggie Smalls.

Yeah.

That is very cool.

It was really cool. I did a deal for Junior M.A.F.I.A., and Biggie came up with Lil’ Kim, and Lil’ Cease. That was not too long before Biggie was killed (March 9, 1997). It’s a legendary shot. I didn’t realize how historic it was going to be back then, but now that I look at it. I’m glad you saw that. I really dug Biggie. He was a great guy. Just a few years ago at ASCAP, we honored Biggie, and I got to be part of that. I was one of the ASCAP guys there, but I actually had a relationship with him. So it was a full circle for me to be at the ASCAP event, having done the deal with him back then.

It was really cool. I did a deal for Junior M.A.F.I.A., and Biggie came up with Lil’ Kim, and Lil’ Cease. That was not too long before Biggie was killed (March 9, 1997). It’s a legendary shot. I didn’t realize how historic it was going to be back then, but now that I look at it. I’m glad you saw that. I really dug Biggie. He was a great guy. Just a few years ago at ASCAP, we honored Biggie, and I got to be part of that. I was one of the ASCAP guys there, but I actually had a relationship with him. So it was a full circle for me to be at the ASCAP event, having done the deal with him back then.

What’s missing in this year’s music industry conference schedule, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, is ASCAP’s ‘I Create Music’ Expo, rebranded as The ASCAP Experience last year (2019). It has been a superb annual conference in Los Angeles for songwriters for years. In 2018, I remember Meghan Trainor did a keynote there with J Kash, and when she walked onstage, she pointed to the spot in the audience where she had sat years earlier when she had attended Expo and was unknown.

Unplanned. It was a conversation between Meghan and J Kash. I kind of set it up saying, “You know Meghan was here something like 7 years ago. She was out there.” And so I introduced them, and Meghan came to the edge of the stage, pointed, and said, “I sat right there.” I could feel everybody kind of inhaling like, “Ahhhhhhh, this could be me.” So she really created a great moment.

Meghan started her career very early, and it took years for her to get her publishing deal with Big Yellow Dog Music, or sign with Epic Records.It’s a big jump for many people in hearing music on the radio or seeing artists onstage or on TV and making the connection that those artists and songwriters are from the same world as they are. It’s another jump to make music on a professional basis. I still get buzzed hanging out at the Songwriters Hall of Fame gala each year with the likes of such songwriters as Don Schlitz, and Jimmy Webb. So the Meghan reveal would have been a big realization to many in that audience.

No question. Paul Williams (ASCAP’s president and chairman of the board) is always the one saying, “Just because you deal with these people all of the time, it doesn’t mean that you have to turn in your fan card.” I am the same way. I am constantly cognizant of, “Wow, I’m in the presence of so and so.” I think about what they meant to me, and what they have meant to the world and what they have contributed to the world. I never lose sight of that.

Your friendship with Tony Bennett goes back decades.

I am very close to Tony, yes.

One thing Tony told you that applies to songwriters is, “Always remain true to yourself in what you’re doing.”

He always says that. I heard him say that not just to me but to other people. As a matter of fact, he’s one of my mentors that I went to discuss the (coming to) ASCAP idea. He was the one that said, “You have to be true to yourself. Think about what you do that can do the most good.” So he was a big help with that. But he talks all of the time about when Mitch Miller (head of A&R at Columbia Records, who signed Johnnie Ray, Percy Faith, Ray Conniff, Johnny Mathis, Tony Bennett, and Guy Mitchell) talked him into recording rock ‘n roll stuff back in the ‘50s.

Tony recorded a pop version of Hank Williams’ “Cold, Cold Heart” with a light orchestral arrangement from Percy Faith that was #1 for 6 weeks on Billboard’s pop chart in 1951, paving the way for country songs to make inroads into the pop market.

“You ruined my song,” he said.

ASCAP has had to pivot due to the COVID-19 pandemic including launching Music Unites Us, a web portal to help its members cope with this crisis, including how to access financial relief through government and other programs and other resources

ASCAP has also had to adjust its programming, conferences, and award shows. ASCAP, for example, transformed its signature ASCAP Experience conference into a free, ongoing weekly virtual event ASCAP Experience: Home Edition that began May 28th. It launched with your conversation with Shaggy and his manager and founder of Cherrytree Records, Martin Kierszenbaum; a discussion of the Billboard #1 hit “Stuck with U” with co-writers Whitney Phillips and Gian Stone; and a session with songwriter Priscilla Renea.

ASCAP more recently combined ASCAP Experience: Home Edition programming to support its Virtual Pop Music Awards, and Virtual Screen Music Awards, recognizing ASCAP’s top songwriters, publishers, and composers of the past year.

Well, we shut down The Experience that used to be called The Expo. But it is such a moving and impactful event unique to ASCAP as a PRO that we just didn’t want to cancel it. So we turned it into a virtual event. It is everything, but the physical interaction of people being involved. So we get to do it more than three days, but it is still the same concept. We started a couple of weeks ago. We do it every Thursday now. I was honored to kick it off with Paul Williams. Paul did an intro and I interviewed Shaggy, and his manager Martin Kierszenbaum. For me, it was great because I signed Shaggy when I was at Warner/Chappell, I would say a year before he did the MCA Records “Hot Shot” album (released Aug. 8th, 2000).

Well, “Hot Shot” reached #1 in the U.S, Canada. New Zealand, and Germany, selling 9 million copies worldwide. It contained “It Wasn’t Me” regarded as Shaggy’s breakthrough in the pop market as well as “Angel,” “Luv Me, Luv Me,” and the double A-sided single “Dance & Shout / Hope.”

That’s 20 years ago now. Just this past year, Shaggy moved over to ASCAP. So not only was I honored to have someone that I have had a relationship with for so long come to ASCAP, but I got to do this interview with the two of them. So every day (of ASCAP Experience: Home Edition) is just a day of the programming of great keynote speakers, conversations with people and panels about songwriting, their business, etc. We are proud that we have gotten to do this.

ASCAP Experience Home Edition on June 25thfeatured film composer Hans Zimmer in conversation with Walt Disney Studios president of music Mitchell Leib; the panel “Breaking Through the Noise: The New Guard of Music for Television” moderated by Michelle Lewis with Torin Borrowdale, Sofia and Ian Hultquist, Amanda Jones and Amritha Vaz; and a conversation between composer Siddhartha Khosla and actor Chris Sullivan.

The ASCAP Experience Home Edition is free to anyone who wants to tune in?

Absolutely. Just sign up (at www.ascapexperience.com) and you can enjoy the experience. Even if you have missed things they are recorded so you can go back and watch things that have already happened.

Prior to this pandemic, ASCAP sponsored song camps, where songwriters got together to co-write and network. ASCAP had hosted Rhythm & Soul and country song camps, where songwriters from two different communities got together. There’s been a Latin camp. Also a series of song camps at Miles Copeland’s chateau, The Castle, located in the Perigord Vert region of the Dordogne in France with the likes of Cher, Jon Bon Jovi, Ellie Goulding and Carole King attending.

For certain, these song camps will re-open after the COVID-19 pandemic recedes because the song camp concept is so conducive to connecting songwriters from varied backgrounds.

Absolutely. They are a great unifier around the world, and we have had so many successes come out of that. One of them in France was Priscilla Renea, Brett James, and Chris DeStefano writing “Somethin’ Bad,” which became a #1 duet hit for Miranda Lambert and Carrie Underwood. That came out of an ASCAP song camp. I couldn’t be more proud when something like that happens.

You oversee a team of ASCAP membership representatives based in Los Angeles, New York, Nashville, Atlanta, Miami, and San Juan, Puerto Rico as well as in the London office. Shine a light on your team members.

Nicole George-Middleton runs our rhythm and soul division, and she is based in New York. She also has a team in Atlanta. We have a really great Atlanta office. Also in New York is Marc Emert-Hutner who is the head of our pop division, and he has a team in New York, and also a team in L.A. The head of our Latin music division, Gabriela Gonzalez, is based in L.A. She has a couple of people in New York and, of course, we have an office in Miami for her Latin music, and we have an office in Puerto Rico.

Mike Sistad is the head of our country division, working from our office in Nashville. We have an amazing team of people in Nashville.

The head of our film and TV division, Shawn LeMone, is based out of L.A. They are fantastic. We also have the head of theatre music, Michael Kerker. He’s bi-coastal working in New York and L.A. We have an amazing roster of not only film and television composers like Hans Zimmer, and Michael Giacchino plus we have Lin-Manuel Miranda (widely known for creating and starring in the Broadway musicals “In the Heights,” and “Hamilton.” So we have a really great presence in musical theatre too. We have a symphony and concert division based out of New York, and the head of that division is Cia Toscanini, a descendent of the great Arturo Toscanini.

Yes, she is the great-grand-daughter of one of the most famous conductors of all time, Arturo Toscanini, who was the music director of La Scala in Milan and the New York Philharmonic, and the first music director of the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Cia’s father Walfredo Toscanini—who died in 2011—was an architect who was instrumental in allowing the Music Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts to obtain The Toscanini Legacy, the massive collection containing the conductor’s personal papers, musical scores, and recordings.

And there’s Simon Greenaway who works in our UK office, and he also reports directly to me.

Overall what are their duties?

Their basic duty is to take care of those specific genres which I oversee. Not only to recruit and retain members, but also they are the ones to handle all aspects of the awards shows, to ensure that a song fits a specific genre, and so on.

If a songwriter has an ASCAP-related issue or wants to know something about ASCAP they can contact one of the genre team members who’d either sort it out or direct them to who they need to speak to at ASCAP?

Yes, they can call Mike, Gabriela or Nicole and say, “I am having an issue” blah blah blah, and they or someone on their team would take care of it. We are really the relationship people with the songwriters, helping with anything that needs to be taken care of. Administrative, even. We are the ones that will say, “I know who to go to take care of this for you.” So we are the contact with the artists and we are the ones to make the ASCAP repertoire strong because we try to recruit to make for a really healthy membership and a strong ASCAP.

Your job isn’t to pitch songs, but you might connect people that might benefit from knowing each other?

We do that all of the time, and we work really closely with all of our publisher members. I love that. They are reaching out to us and we are reaching out to them. I just named all of these styles of music. This is one of the things I was always thinking about because, if you look, I signed people like Cassandra Wilson and Billy Ray Cyrus. I love all music. So this job…I work with all of my team, and I have Nicole, Mark, Mike, Gabby, all of them; I can’t say enough about them. They really are the lifeblood of the membership.

A comment you made to Billboard’s Melinda Newman in 1995 has long resonated with me. You said, “There are fewer and fewer singers that are just singers only. I mean that Bing Crosby is gone.” That was evident at the time and is certainly true today being that there are few artists who don’t write their own songs, making it more difficult for music publishers and independent songwriters to pitch songs.

Yeah, and I was someone who was trying to pitch songs all of the time. In 1995, I was at Warner/Chappell. So I had already been through two other music publishing companies. I loved being a song plugger but it was turning into being difficult. Artist songwriters were themselves writing more and more songs; producers were writing songs with the artists.

At the same time, the film and TV sync market hadn’t exploded yet for contemporary music; certainly not for hip hop, country or Latin musics.

Correct which became the new song plugging. I used to tell everybody that I worked with that no matter how difficult it is or how few cuts you may get, if you come in in the morning thinking that you are not going to get a cut, then you are not going to get a cut. I would always promote that through my teams wherever I was, and I would do it myself. I would always be plugging songs. You do that, and you get songs covered. I just don’t think that was a great era. I would have loved to have been a song plugger in the ‘40s. It must have been something else.

There was considerable exploitation within Tin Pan Alley back in its heyday.

I am talking about the Hollywood idealized version.

You are thinking of the likes of Sammy Cahn, who with Jules Styne, Nicholas Brodzsky, and Jimmy Van Heusen, co-wrote some of the best-known popular songs of all time including, “Saturday Night Is The Loneliest Night Of The Week,” “Time After Time,” “Love And Marriage,” “Come Fly With Me,” “Only The Lonely,” and “September Of My Years.” You are thinking of a time when a songwriter got a call, “Frank needs a song.”

Yes, that’s exactly what I am thinking of. It’s funny, but you know the (1944) movie “Going My Way,” with Bing Crosby as the priest trying to pitch a song to a publisher that I think was played by William Frawley (unaccredited, playing publisher Max Dolan). His way of turning down the song (“Going My Way”) was, “Our catalog is all filled up” is what he said. I love that to this day. How does a catalog get filled up?

My wife Anya Wilson, while 22 in 1970, worked for German-born, British music publisher David Platz at Essex Music Group which owns copyrights popularized by the Rolling Stones, the Moody Blues, the Move, Procol Harum, The Who, Lonnie Donegan, David Bowie, and Marc Bolan. One of the veteran publishers, George Seymour, general manager of Campbell-Connolly, admonished her as a song plugger, declaring, “You call yourself a song plugger. You can’t even play piano.”

That’s right. Song pluggers used to demonstrate the songs to people. I read that way back that song pluggers would be in the theatre, and when the singer was singing the song, they would get up and say the name of the song out loud and then actually start singing along with the singer onstage; giving the impression it was already a popular song already, and you used to run out, and buy the music sheet

Fats Waller’s son, Thomas Waller Jr., told me of his father going to music publishers’ offices on his way home. Playing a song and selling it for cash at the first office. Playing the same song a different way for another publisher at their office, and so on. He’d arrive home with $600 and throw a big house party. It’s possible he composed many more popular songs and sold them to other performers when times were tough. He copyrighted over 400 songs, many of them co-written with Andy Razaf. Fats Waller’s best-known songs include “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and his first success, “Squeeze Me” (1925), written with Clarence Williams.

You are telling me he was misbehavin’.

After your 13-year run with Warner/Chappell, and before coming to ASCAP, you launched your own firm, MPCA Music Publishing in 2006, encouraged by your friend, legendary independent publisher Billy Meshel. You bought Billy’s Music & Media International catalog which contained the complete works of the revered bluesman, Robert Johnson.

(During his earlier tenure at Famous Music, Billy Meshel co-wrote one of pop culture’s most famous songs, The Brady Bunch’s “Time To Change” with Chris Welch and Raymond Bloodworth; as well as penning the lyrics to “Come Live Your Life With Me” (aka “The Godfather Waltz”)” written with Lawrence Kusik and Nino Rota. In 1976, Meshel became president of the newly-formed Arista Music Publishing Company. When BMG Music Publishing acquired Arista Music, he served as president until 1988, leaving to become president/partner in All Nations Music Publishing, until forming, with John Massa, Music & Media International. Billy Meshel died in 2015.)

MPCA grew quickly into a leading US independent publisher through agreements with Lehsem Music, Sunset Boulevard Entertainment, Sammy Cahn (via MGM), and Snuff Garrett Music as well as music by the Smithereens, Exene Cervenka, including those of the seminal American first-wave punk band X.

There were such evergreen compositions as: “I Swear” written by Gary Baker and Frank J. Myers, recorded by All-4-One and John Michael Montgomery; “I’m A Fool To Want You,” composed by Frank Sinatra, Jack Wolf, and Joel Herron; “The Second Time Around” with words by Sammy Cahn, and music by Jimmy Van Heusen ; “Leave (Get Out),” written by Soulshock, Kenneth Karlin, Alex Cantrell and Phillip “Whitey” White of The Trackheads, recorded by JoJo; and “After The Lovin’” composed by Ritchie Adams with lyrics by Alan Bernstein, recorded by Engelbert Humperdinck.)

The coolest of cool acquisition from Billy was the catalog of Robert Johnson, the most important blues singer that ever lived. The catalog included “Sweet Home Chicago” (1936), “Cross Road Blues” (1936), “Hellhound on My Trail” (1937), and “Love in Vain.” Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, and Robert Plant have each cited Johnson as a key influence. Many of the 29 songs in the Robert Johnson catalog have been covered by other artists. The list of Johnson covers is endless.

Yes sir.

A few years ago I interviewed Boston promoter Don Law for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. On his office wall, he had a Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) award for the cassette of “Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings” which peaked at #80 on the Billboard 200 album chart. The album sold more than a million copies, and won a Grammy Award in 1991 for Best Historical Album. The 41 Johnson tracks recorded in two sessions in Dallas and San Antonio, Texas for the American Record Company (ARC) during 1936 and 1937 were recorded by Don’s father, also named Don Law.

Wow. That’s incredible.

Don Law Senior also recorded Bob Wills’ “San Antonio Rose,” in 1938 which became his signature song.

(As the head of Columbia Records’ country music division in Nashville through most of the 1950s and 1960s, Don Law was among the most important and successful producers in the annals of country music. Among the artists he signed and worked with were Carl Smith, Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price, Johnny Horton, and Johnny Cash.)

What was your thinking in launching MPCA Music Publishing? Did the years of working for other music publishers give you the confidence to venture out alone? That you thought, “I can do this myself.”

Well, I had been at Screen Gems/EMI, Polygram, and Warner/Chappell, and at that point, things were changing at Warner Music Group. At the same time, I had at least two people who are important to me. One was Billy, and the other was Frank Miltary (senior VP for Warner/Chappell Music Publishing). He said, “At this point, you should try being in the John Titta business. A lot of people come here because you are here.” And I had this opportunity through Billy. I had done a deal for one of Billy’s previous catalogs (All Nations Music) when I was at Polygram. He had built film catalogs and wanted to sell them, and I knew an investor that had said, “Hey, if you ever want to go into business.” So I made a decision in terms of “This could be my moment to do this,” and that’s what I did. So I had a single investor, and I started building something. I started with Billy’s catalog which had Robert Johnson’s catalog which was the jewel in his crown. That is really why I decided to do it. I didn’t want look the rest of my life thinking that this is something that I should have tried. So I took a daring stab at it.

Pretty incredible to handle the Robert Johnson catalog.

When is something like that going to be available again? So there’s some amazing things in that (MPCA Music Publishing) catalog. A piece of the song “I Swear,” the All-4-One song; “After The Lovin’,” the Engelbert Humperdinck song. There’s some great songs there. The Smithereens’ catalog which was weird because I had done a publishing deal for the Smithereens at Screen-Gems/EMI so I was friends with Pat DiNizio ( the late lead singer and songwriter of the New Jersey rock group). So that was in the catalog and a ton of other stuff. The Cowsills’ hit, “The Rain, the Park & Other Things” (co-written by Artie Kornfeld and Steve Duboff) was in the catalog. So I was excited. My dream was to build sort of a little Warner/Chappell. Some blues stuff, some pop stuff. I went and got a great catalog that MGM had of Sammy Cahn, all those film things like “Second Time Around,” and “I Fall In Love Too Easily,” and I just started to build a little catalog.

At ASCAP your role is being THE great connector, hooking up ASCAP publishers and songwriters with every spoke in the music community. As a music publisher, you were, as many publishers are, a song plugger but also a great connector too, having your songwriters co-write and meet with other songwriters or with labels, managers, agents, whatever it took.

For example, you have a relationship with Carole King that goes back to your time at Screen-Gems/EMI. When the Minneapolis-based trio Semisonic was set to record its 3rd album, “All About Chemistry” in 2000 you suggested involving Carole to the band’s singer/guitarist Don Wilson. So “One True Love” was co-written by Dan and Carole who also did the vocals and electric piano on the recorded track. That wouldn’t seem to be a natural match-up for some.

I had signed Semisonic, and they were working on a new album—this is how this happened—and I had spoken to Dan’s manager, and then I got on the phone with him and Dan, and I asked, “Who are you thinking of working with?” And Dan said, “I really don’t know. Do you have any ideas?” I said, “What about Carole King?” Dan was like, “What are you talking about?” So I put them both together. Then they wrote “One True Love” together.

In songwriting circles, Carole King is like the most desirous girl in school. People think she’s already got a date for the Prom, so she wouldn’t be interested in dating. “She wouldn’t possibly be interested in co-writing with me.”

Oh, because of my relationship that I so grateful for, I put Carole with Chris Difford, Paul Westerberg, and Dan Wilson. Carole co-wrote “You Can Do Anything” with Babyface that I cut with Donny and Marie Osmond on a country album I worked on. So Carole was always open to collaborations like that. One of the most wonderful things out of my publishing years was meeting her while at Screen-Gems/EMI. I had gotten a commercial for “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” (co-written with her former husband Gerry Goffin), a jeans commercial, and her manager called saying, “Carole is coming to New York, and she wants to meet you.” Boy I will never forget that lunch. Her manager told her that I was reaching out to people who were legendary in the (Screen Gems) catalog. I was so excited about that lunch.

Soon afterward, you were promoted to the position of professional manager at Screen-Gems/EMI. Were you still in the tape room at the time you met Carole for lunch?

I think I was just out of the tape room. Or maybe I was still in the tape room.

You were smart enough to avoid the mailroom there.

I avoided the mailroom. I was working as a musician at that time, so my day job was being in the tape room. Wow! I was in the tape room surrounded by these catalogs of sound like “The Look of Love” (composed by Burt Bacharach and Hal David) there. I pitched that, and I got it covered by Grover Washington Jr.

After working at Screen Gems for four years, you worked at PolyGram Music Publishing as its VP of A&R where you had a terrific run. You signed Bon Jovi, Richie Sambora, Brian McKnight, k.d. lang, Billy Ray Cyrus, Jimmy Webb, and members of a group called Mother Love Bone that became Pearl Jam. Additionally, you helped develop R&B artist Brian McKnight; worked on the 1991 “Two Rooms” tribute album that celebrated the songs of Elton John and Bernie Taupin; and had a great good cover hit with “Save The Best For Last,” written by Phil Galdston, Wendy Waldman, and Jon Lind, with Vanessa Williams.

Ironically, I co-wrote a song “Memphis” with Johnny Reid and producer Bob Ezrin which Johnny recorded for his “Reunion” album in 2017, and you back then signed Bon Jovi keyboardist David Bryan who, with Joe DiPietro, co-wrote the musical “Memphis” that ran on Broadway from October 18, 2009, to August 5, 2012. The show was nominated for 8 Tony awards for the 2010 season, and won four, including for Best Musical, and Best Original Score.

I have to tell you that “Memphis” was…you know what I loved about that was David’s acceptance speech at the Tonys I was so moved. Of course, he invited me there. His acceptance for the best original score was about me being his publisher, and he mentioned me, and his story was true. We were always trying to—I’m very close as well to Jon (Bon Jovi) and Richie (Sambora) who is like my best friend…So I was always picking songs for David. It was really tough getting him covers. So I introduced him to somebody that was looking for someone not involved in musical theatre. They wanted somebody rock. David had looked at me, “A musical? What’s that?” I said, “Like Broadway.” I took him to a couple of shows, and he met with various people doing shows. One of them was Joe DiPietro, who wrote the book and the lyrics for “Memphis.” Literally the day after he met Joe, David called me, and played me the song that closes the show, “Memphis Lives In Me.” Then the show took place years after that moment. To me, as a publisher, what happened was better than just getting a cut. I literally took somebody and pointed them in a direction. It was a new direction for him creatively.

David and Joe’s musical “Diana, about Princess Diana” was expected to begin previews on Broadway on March 2nd (2020) followed by an opening March 31st, following a tryout production at the La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego last year.

Yes, and David has a whole new career in the world of Broadway, and I am proud of that.

Well, I figure you are going straight to hell for signing Kid Rock while senior vice president / general manager of Warner/Chappell Music in New York.

He’s not the guy I thought he was back then.

(From 1993 – 2006, while senior vice president/general manager of Warner/Chappell Music, in New York, John Titta also signed Trey Songz, Fat Joe, Missy Elliott, Collective Soul, India.Arie, Gavin DeGraw, Cassandra Wilson, Dan Wilson (Semisonic), Uncle Kracker, Shaggy, Simple Plan, Duane Eddy and Bruce Hornsby.)

I’m teasing you. I’m a big fan of Kid Rock’s early music.

It was exciting back then. It was an exciting moment. He was different.

I just love his Lynyrd Skynyrd mashup, “All Summer Long” and his duet/co-write with Sheryl Crow of “Picture.” And seeing Kid Rock performing “Honky Tonk Women,” “Little Queenie,” and “Whole Lotta Shakin´ Goin´On” with Jerry Lee Lewis on the 2006 show “Last Man Standing” is quite amazing.

The first time he came to New York is where I met him. I had seen him perform in Detroit, and our first meeting was him and I playing Hank Williams songs together.

I recall Kid Rock and Hank Williams Jr. and the Bama Band together in 2002 on “CMT Crossroads” which paired country stars with artists from other musical genres. One of the greatest music shows I’ve ever seen. A great performer.

Correct.

Kid Rock was quite close to Atlantic Records’ co-founder Ahmet Ertegun. When Ahmet died in 2006, he joined hundreds of mourners at the funeral in Istanbul.

Yes. I did know that.

How did you end up doing background vocals on Ringo Starr’s recording of “I Wanna Be Santa Claus” in 1999?

That’s all Mark Hudson’s fault. “Hey, you want to be in the > Choir” and I was like, “Yeah.” I sang on a couple of passages.

Very cool.

It was very cool.

(For a decade, starting in 1998, Mark Hudson was the primary driving force as producer and composer behind Ringo Starr’s career as a recording artist. Hudson produced or co-produced nine albums for Ringo Starr.)

I was surprised to find that you got to know the late “Godfather of Soul,” James Brown.

I would say that this was probably back in the ‘90s. A lot of his catalog from other publishing companies had reverted back to him, and he had part of a catalog at Warner/Chappell. Myself and Don Biederman (head of business affairs) went to Georgia to meet with James Brown and his people. That was the most spectacular meeting. Talk about meeting somebody larger than life. He took a particular liking to me. Whenever he would come to New York, a gentleman called Mr. Robinson would call me, and say, “Hold on, I have Mr. Brown,” and he would get on the phone. By the way, he never called me John, and I never called him James. I was Mr. Titta, and he was Mr. Brown. He’d be like, “I’m doing ‘Good Morning America,’ I want you to come.” So I got very close to him. He came up to the office. When he passed I was invited to view the body at The Apollo. Warner/Chappell helped him record “The Great James Brown Live at The Apollo 1995” album. We did it over five nights. So for those nights, I was at The Apollo with Mr. Brown and it was really stunning.

We know about the golden moment when a music publisher lands a cover or they hear their songwriter’s song on the radio or on TV or in a film. Tell me about the lonely moment sitting in a chair as a label A&R person, manager or artist is listening to a song demo, and evaluating it. You are thinking, “Oh jeez, where is this going?”

Well, it would be a frustration. I like that you term it loneliness because when you believe in a song…One part of it is that it makes you start to question what you are hearing, and there are some songs that never get cut, and some songs that do get cut. I have gotten many letters from people say, “Jeez, John nice song, not a hit,” that have gone on to be hits. The satisfaction of that happening a few times makes up for the loneliness, as you call it, or the frustration of it when it doesn’t happen.

Fred Bronson’s book series, “The Billboard Book of Number One Hits,” provides the back story behind every #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart since 1955. In so many cases, the hit status wasn’t anticipated. Either the artist, the producer, the manager, or the label didn’t want the song picked as a single or even recorded. Often the hit was the B-side and was flipped over. Even savvy industry folk don’t always know a hit.

Conversely, there are times that you just know a record has a shot at being #1 as I did when Bryan Adams’ manager Bruce Allen played me over the telephone “(Everything I Do) I Do It for You,” co-written by Bryan, the late Michael Kamen, and Mutt Lange. Of course, it went on to #1 in over 23 countries, and has the longest unbroken run at the top of the UK Singles Chart, spending 16 consecutive weeks at #1. So there are times that you just know a record is a hit.

Yeah, that’s true. When I was a publisher most of the people I signed the reason why I was signing them wasn’t necessarily because they had a record deal or the album was coming out or whatever because I was able to develop a lot of people. But, even at the worst, I was always thinking to myself about the person that I was signing–and I shared this with them sometimes, and I don’t think that they understood the first time I really explained it to them—“If your record does not happen while you are developing your artist career, my job is going to be that I’m developing your songwriting career. My goal is that you will be able to do this for the rest of your life. somehow. No matter what happens here.” One act took it almost as an insult. “You don’t think that my record is going to happen?” I was like, “No no no. I do. That’s why I signed you. But I want to make sure that you can do this as a career somehow.” I would always, even before the success or the (label or radio) support that would happen, I would pick one or two songs on each project, and I’d go, “I’m putting this on a little disc or a cassette” and I would make it my song plugging thing. I was ready to kind of save the project, and plug in a song (elsewhere). Those are particularly satisfying when something like that would end up being a success.

In the earliest days of their songwriting partnership, Lennon and McCartney expressed a desire to emulate the successes of such Brill Building composing duos as Goffin & King, and Leiber & Stoller in having their compositions recorded by other artists, With the encouragement of the Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, they pitched their songs deemed unsuitable for the Beatles to fellow artists like Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas (“From A Window”), Cilla Black (“Love of the Loved”), P.J. Proby (“That Means A Lot”), Peter and Gordon (“A World Without Love,” “Nobody I Know,” and I Don’t Want To See You Again”), and the Rolling Stones (“I Wanna Be Your Man.”)

There are so many artists like Amanda McBroom (“The Rose”), and even Jackie DeShannon (“When You Walk in the Room,” and “Bette Davis Eyes”) that made more money as songwriters than as artists. Often artists are paying costs of recording, touring, and so on back to labels. Music publishing income, even being split with a publisher, may be deemed as more direct. In debt as artists, they were able to create significant income on their songs as a songwriter and/or as a co-publisher or publisher of their own works. It takes artist/writers a bit of time to realize that

Absolutely. I’ve had had cases where the songwriter came back, and said, “I get that meeting that we had that day.”

Traditionally, music publishers owned the entire publishing of a song but in more recent years co-publishing, largely 50:50 splits with songwriters, are the norm. Was there a change with music publishers in their commitments as they moved in recent years from full publishing to co-publishing, particularly with newer songwriters? After all, with co-publishing, the publisher is expected to pay advances and do most of the spadework despite now splitting royalties. Was there a pull-back in developmental support?

Well, I can speak for myself, and I would say that even if it was an administration deal I would never pull back because for me where I am sitting…Look, I believe that if this writer is trusting me or trusting my company and where I am taking care of the music regardless of the status of that particular deal, I want to perform for them. My job was to perform for that person and get their songs in places. Let’s say it’s an administration deal, probably that is the best example…

Yes, but an administration deal is likely with a more established songwriter. There’s already income being generated. I’m talking about deals with newbies.

Newbies, the single answer is that it would never color my attention to what kind of a deal that it was. To me, it was either that it was a great song or it’s not a great song. I want to make it successful with somebody I don’t need to get this person a record deal. I want to develop them into something. I want to get a song cut. So it was about the artistic endeavor.

So it didn’t matter if it was the half loaf or the full load.

Right. “What kind of a deal is this, and then I will pay more attention to that song or songwriter.” No, I was never like that.

There were publishers that would pull back support without full publishing.

I would imagine, yeah. Yes, of course. “We have more of a vested interest in this, this is what you should concentrate on.” I never really would do that.

When I talk with an artist who is also a songwriter, they usually talk of being an artist, not about their role as a publisher or co-publisher of their music. They are dumfounded if you ask. They don’t know what I’m talking about. I do wish artists that are songwriters, who own or co-own their publishing, more aggressively promoted their songs. That they think more about being not only an artist, but also being a songwriter, and a music publisher.

I think that is part of the mentality of a different generation of songwriters, but it does go back to what I was saying before that you do try to instill that in someone. “Okay you are working on your artist’s career, but also let’s think about your songwriting career, and let’s think about how you are going to be treated if you stay with your writing, and we make sure you are getting as much value out of what you created.”

Maybe it comes down to the mentorship, and the direction of the music publisher in the way that they see the role of the songwriter. Making them aware of those opportunities. As I said, there are some artist songwriters that are very aggressive about pitching song. Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, Jimmy Webb, Bryan Adams, Randy Bachman, and Kris Kristofferson are among the most persistent that I know.

Listen I used to run into artists in restaurants and ask, “Are you looking for any songs?” I used to do that all of the time.

Years ago, songwriter Hal David told me a wonderful story, “When I became president of ASCAP, the first call that I made from our building on Broadway was to Irving Berlin. He was always the #1 songwriter (at ASCAP). He returned my call. I remember that he said, “Why do you want to be president for? You are such a good songwriter.”

I will ask you a similar question. You were such a wonderful music publisher why did you decide after MPCA Music Publishing to work at ASCAP in 2013?

I don’t want to go Jimmy Stewart on you, but I will say that I had worked my catalogs for about 6 or 7 years. I was the creative person, I had an investor. We had done some really good things. When the market went a little crazy in 2008, I started to create—because we were kind of not buying any catalogs at that second I kind of took what I had and was making albums. I was creating a masters’ catalog (MPCA Records) to match the publishing catalog. So I did a Dionne Warwick album with my standard stuff, with my Sammy Cahn stuff.

Dionne’s “Only Trust Your Heart” album in 2011?

Yeah. that was the album. I did a Robert Johnson project with Todd Rundgren (“Arena” in 2008). And I did a great pop-country album (in 2011) with Donny and Marie Osmond (“Donny & Marie”) which sold a lot of records. It was a really big record. I used all my relationships in the world. I got Buddy Cannon, who was a producer for Kenny Chesney, to produce the album. I got songs from friends of mine like Carole King and Richie Sambora, I was handling the administration of his solo stuff then. Buddy made this really great album. So we had built this to be this certain thing, and in the middle of due diligence, and kind of flipping the company, I was kind of going to go with it wherever it went. At that moment, I was approached by ASCAP when I was in play. My first inclination was to say no. It was not the type of (career) path that I was on. I had broken this catalog. I was doing this label thing. I will say that they were very complimentary. They said that they would wait to see what I wanted to do. I started learning more about ASCAP I started to see all the work that they were doing on the copyright reform side. That really spoke to me, the advocacy. I knew in my career as a publisher what ASCAP would do for a writer. I sent people there all of the time, especially if I was developing a songwriter I’d use the PRO as part of our team.

Were you an ASCAP writer?

Yeah, I had stuff that I had written early on there because I had started as a music teacher.

Coming to ASCAP and overseeing its educational programs and other things is a return to your music teacher roots.

You actually hit upon it. As that summer went on, and the more that I was learning, I started to think about myself in the role. First of all I felt grateful, and I mean this sincerely, that I had gotten to a point that when I get up every morning, that I do something that I love every day. And that is all because of songwriters. There’s nothing more important to me than songs, and songwriters. So the idea that everything that I had done would be used, and would be in play in this position, and that I would be doing something good for the people that have afforded me to have a wonderful life, and that I think do so much good in the world, appealed to me. I always say this thing that when I try to explain what it means to me that life is so unpredictable, and the comfort of the predictability and the comfort of that three minute or whatever song that people make does so much good for people around the world that I feel that it is God’s work. I feel like it is such an important thing. And the position at ASCAP just felt like a giving back to me, but also I’d be using all of the tools that I had learned in my life in one place.

You grew up on Staten Island?

Yes sir.

Staten Island, sometimes called “the forgotten borough” by inhabitants who feel neglected by the city government, has the highest proportion of Italian Americans of any county in the United States. To add a sense of reality to the wedding scenes of “The Godfather,” the wedding of Don Corleone’s only daughter Connie, Francis Ford Coppola in 1971 shot the scenes guerilla style in two days in a Staten Island neighborhood with almost 750 locals as extras. The house used as the Corleone household and the wedding location was in the Todt Hill neighborhood of Staten Island. The wedding sequence was staged on the house’s palatial lawn. You were one of the young kids in the crowd dancing.

When you see the movie, if you look at the band, the man playing the clarinet in the middle of that band was Nino Morreale who was one of my music teachers. Outside of the actors, everybody who is up there filming were locals. Yeah, I’m one of the kids. Everything goes by so fast. There were two days here on the island that were legendary. It was up on one of the hilly parts of Staten Island. The house is still there. The caterer who brings in the cake was a local restaurateur. Everybody up there were locals from Staten Island. It was pretty legendary. Of course, nobody knew that what’d happen to the film. Back then when we went up to the shooting site, there were all these Italian-Americans organizations (led the Italian-American Civil Rights League) protesting the making of the film. Nobody knew that they were making the Mona Lisa up there.

You have talked about growing up in a household where there were instruments everywhere—mandolins, ukuleles, drums. Were either of your parents musicians?

No. My dad played the drums in his early life. I never really knew that. I found that out later. My thing was that I was obsessed with music. I was obsessed with the the radio. Obsessed with the Beatles. Like you, I could tell you so many things that people would think are not important; things I learned reading the labels and knowing who played what. I just found that to be something that was so poignant. So when talk about my influences that my life as I grew because at a certain point I joined the local musicians union and I saw that I would get more sessions if I played more instruments.

Not to mention that you might be tapped to be the session leader which is more money.

(Laughing) So I literally did some sessions where I could work really quickly. Now I am sitting here surrounded by my mandolins, ukuleles, and guitars and keyboards.

One of your mentors was jazz guitarist Chuck Wayne, a member of Woody Herman’s First Herd, and also the first guitarist in the George Shearing quintet, and Tony Bennett’s music director and accompanist. He was employed as staff guitarist for CBS in the 1960s for two decades.

Chuck Wayne also lived on Staten Island, and I took lessons from him. I started teaching. I was trying to go to get a Master’s degree to get a teacher’s license. You had to have a certain amount of time to get that. That was a tough thing. I was trying to pay for it on my own, and Chuck was the one who said, “I get lots of calls from studios and, if you are looking to make some extra money, you can handle it.” So I started doing sessions.

What type of sessions?

I did a lot of commercials. I did do some things with Gregory Abbott. I did some work at Unique Recording Studios (operating in New York City from 1978 until 2004). Bobby Nathan’s place back then

Unique Recording was a studio that Bobby ran with his wife Joanne located just off of Times Square in the top three floors of the Cecil B. DeMille Building

I was doing mostly commercials.

Sessions for radio and TV commercials were done at a quick pace in those days.

It was great, and I was learning about if you are a musician you’d get placed on many shows. If you were the key person, you got paid more than if you were in the background. I started doing really well and, as much as I loved being a music teacher, I was doing the thing that I really loved.

Not to mention that residual payments could add up.

Yes. And I started thinking to myself, and this is really a sad thing to say because teachers are so important to the world, but “I’m making all of this money so I can go back to school so I can get my Masters so I can keep a job in which it is difficult to make a living.” So I made a conscious decision to be a professional musician.

American music publishers and songwriters are currently locked in a legal battle with Spotify, Amazon, Google and Pandora (but, notably, not Apple) over how much they will get paid in the United States. The battle is because these streaming services have appealed a government-mandated Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) decision from November 2018 to raise mechanical streaming royalties for five years from 2018 onwards; a nearly 44% rise in streaming mechanical rates over 5 years in the U.S.

We all believe that the contributions of music creators should be valued higher. I don’t know if I am the guy (at ASCAP) to speak about the specifics, but go on.

I don’t think you are either but, in general, songwriters and music publishers have long led the fight for proper compensation. People talk about the music label system of yesteryear in a similar way that Hollywood denigrated artists, producers, and other creative people in the studio era of the ‘30s and ‘40s. There are those who argue that Spotify, Amazon, Google, Pandora, and Apple are different from the labels of the past. No, they are not. They control music by controlling the distribution process

Today, with diminished income from recordings, and no live income now, artists are waking up to realize that these streaming services are replicas of the gatekeepers of the past. Eventually, they may be forced to finally join the publishing sector at the table in fighting with the streaming services. In the past year, it’s become increasingly harder being an artist to make a living, but It is harder today than ever making a living purely as a songwriter.

Harder, but I believe going in the right direction, to be honest.

Yes, mechanical and synchronization revenue is growing faster than performance because streaming continues to grow, and more of the streaming revenue is being categorized as mechanical. Also, streaming revenue is derived on a global basis so there’s considerable reach. Furthermore, more artists have control of their masters, and songwriters have more control of their music publishing. Still, while leading publishers and songwriters alike have had to fight in the trenches for years, successful artists are only now facing leaner pickings.

That is true.

I recall a time when new streaming platforms being launched did not understand that after paying for recorded master rights that they also had to pay for mechanical and performance rights though music publishers. That floored them at the time.

A lot of the world only thinks that whoever is singing the song is the one who wrote the song.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is a co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.