Data shows that interactive streaming has become the dominant form of music consumption, largely replacing previous means of listening, and causing us to look back at the less than lucrative (albeit brief) fourish year period of music downloads.

________________________

Guest post by media and tech consultant Bill Rosenblatt from Forbes

The latest revenue figures from the music industry tell us that we’ve entered a new era: the era of interactive streaming. Interactive streaming music services — Spotify, Apple Music, Napster, Deezer, Tidal, etc. — now account for the majority of recorded music industry revenue and are growing at better than 50% per year. We’re now in the fifth era of recorded music, after the eras of vinyl, tape (8-tracks and cassettes), CDs and music downloads.

What the revenue numbers tell us about the previous era — the era of downloads — is just as interesting as what they tell us about the future. Back in the mid-2000s, music downloads were the birth of the digital revolution. But the numbers say that the download era is likely to go down in history as a brief glitch — a transitional phase between physical products and cloud-based music that did the industry no favors at all.

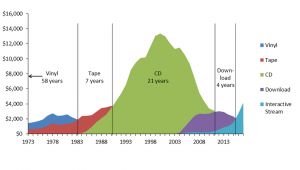

The five eras of recorded music: vinyl, tape, CD, downloads, and interactive streaming.

Revenue in $millions. Source: RIAA.

This chart shows the five eras, which are defined by the music delivery format that produced the most revenue during the period. The first era was vinyl. Vinyl (actually shellac) recordings came out before the turn of the 20th century, but the industry really came into being in 1925 when vinyl disc speed became standardized at 78 rpm, making it possible to play discs from any label on any record player. In the late 1940s, 33 rpm LPs and 45 rpm singles came along, and vinyl began to replace shellac.

Next came the tape era. Eight-track tapes came along in the mid-1960s as a way of playing music on demand in cars. Then, in the early 1970s, cassettes became capable of good sound quality in a more convenient package. Not only did cassettes supersede 8-tracks in the car, they also became viable alternatives to vinyl in the home. But the innovation that really lifted cassettes’ importance was the iconic Sony Walkman in 1979. This introduced the world to high-quality personal portable on-demand listening; by 1983, cassettes led the industry in revenue.

That same year, the CD hit the North American market. CDs outdid both cassettes and vinyl with superior sound quality, easy access to individual tracks, and increased capacity. They became huge — not least because many people repurchased digitally remastered titles on CD that they already owned on scratchy vinyl or mangled cassettes. CDs didn’t just grow industry revenue at normal rates, as cassettes did over LPs; they took the industry to staggering heights.

Music downloads appeared in the late 1990s, at the height of the CD era. Downloads took up no storage space at all (apart from that of a hard drive) and were easily portable and transferrable, even if the sound quality of MP3 files tended not to be as good.

But very few music downloads in the late ’90s were legal. By that point, CDs had a run of 15 years of double-digit growth and nine years as the most lucrative recorded-music format; the record labels weren’t interested in supporting anything that would disrupt that momentum. They were especially afraid of supporting a format that was so easy to copy without authorization. So instead of embracing downloads, the labels pushed back against them with lawsuits, overly onerous licensing deals with emerging music services, and DRM technology requirements.

It wasn’t until 2004 that Steve Jobs was able to coax the major labels into backing a simple, attractive model for music downloads with iTunes. Download revenue started growing at the same steep rate as CDs had done during the 1980s. But the growth didn’t last; revenue started leveling off in 2008.

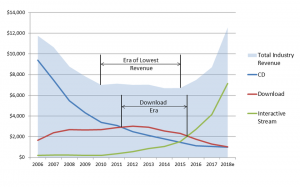

Downloads lasted for only four years as the leading source of revenue in the recorded music industry. That’s the shortest era in the industry’s history. And while it’s tempting to think that the brief length was due to rapid technological changes that usher in the next shiny new thing more and more quickly, that’s just not the case here. CDs lasted much longer than cassettes; and as the chart above indicates, interactive streaming is growing more rapidly than CDs or downloads in their heydays and should be the dominant source of revenue for some time to come —especially since we have no idea what technology will come next.

Several factors contributed to the decline of downloads; one was the economic slowdown of 2008. But other factors were more important. One was the unprecedented ease of copying files and transporting them around the Internet. DRM technology was meant to inhibit that, but research on how effective it was has been very limited; my own research shows that the industry’s 2009 shift to selling DRM-free downloads wasn’t correlated with any significant changes in revenue.

Another factor that turned people away from commercial downloads was the growing sense that when you bought them, you didn’t really “own” anything. The idea of building a “library” of digital files didn’t turn out to be so appealing when you couldn’t hold anything in your hands or point to shelves full of music, there wasn’t anything special about owning things that could be copied so freely, and it became a hassle to keep all those files synced across all your devices.

Ultimately, interactive streaming services dispensed with the veneer of ownership entirely, replacing it with unlimited access to a massive library of music for as long as you kept your subscription active. Interactive streaming had been around since the early 2000s, but it took three later developments to make it popular: smartphones (2007), 3G wireless service (2007-2010), and the massive hype that accompanied Spotify’s 2011 launch in the U.S. market. Accordingly, download revenue started to fall in 2012.

On the other hand, the great selection and convenience of interactive streaming threw downloads’ lack of ownership benefits into sharp relief, and music fans began to look for formats that provided those benefits. Around the same time as interactive streaming started its hockey-stick growth, vinyl started to come back to life — after having been all but dead from the 1990s through the mid-2000s. And the precipitous decline in CD sales started leveling off.

In fact, as the projections in the figure above show, download revenue should drop below CDs by next year. (It’s already less than revenue from all physical products — CDs plus vinyl.) After that, we should see an end to downloads as a commercially viable format. In fact, the industry is rife with rumors that Apple intends to stop selling music downloads sometime next year.

At the end of the day, neither the industry nor consumers have valued downloads very much. Downloads were a convenient stopgap during a time when Internet access was slow, not pervasive and not continuous; and the more complex streaming technology had yet to be fully developed. But as the figure above also shows, the download era of 2011-2015 coincided almost exactly with the worst period for total industry revenue (adjusted for inflation) since the RIAA began compiling data in 1973.

Downloads may have long-term appeal among certain tiny niches, such as collectors of obscure music that isn’t available on the streaming services or that minority of audiophiles who like 96KHz/24-bit FLAC files and don’t prefer vinyl. But otherwise, downloads should soon fall off the map, and few will miss them.

Bill Rosenblatt runs GiantSteps Media Technology Strategies, a consultancy that focuses on digital media technology, business models, and copyright. Check him out on LinkedIn or Twitter.